Greener than all the American dollars that helped to buy them,

the meadows of Oxfordshire undulate gently toward a misty horizon, dotted with horses, cows, and

sheep in a picturesque tableau. Perched on a slight rise, its lawns presided over by imperious

roosters, an ancient stone manor house conceals a cozy domestic scene: barking dog, pert blonde

wife, flaxen-haired thirteen-year-old daughter wearing a satin baseball jacket emblazoned with

the word "Chess."

Years ago, Tim Rice, flushed with his first big success, evicted the cows from a derelict barn

behind the newly purchased house and turned it into his studio. Back then, as the co-author of

Jesus Christ Superstar, he was the toast of two continents; he and his partner, Andrew

Lloyd Webber, went on to score again with Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat

and Evita.

After Evita, however, the composer and lyricist drifted apart, and while Lloyd Webber

went on to write such mega-hits as Cats and Phantom of the Opera, there has been

less fanfare for Rice. Not that he or his surroundings are unimpressive; a huge man with flyaway

silvering hair and the bulging belly of an eighteenth-century country squire, Rice is very much

the twentieth-century lord of the manor. His studio shelves are laden with sophisticated sound

equipment, his walls crowded with platinum and gold records, his desk and tabletops littered with

citations and awards—except that if one browses long enough amidst the clutter of contemporary

success, one begins to sense the faint but disquieting aura of a career already viewed in

retrospect.

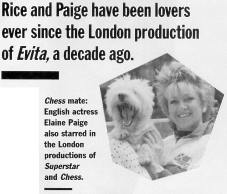

Among the aging memorabilia is a photograph of Elaine Paige as Eva Perón, an arresting

image that dates back to the 1970s. It marks a momentous event in Rice's life; notwithstanding

the pretty family in the big house, he and Paige have been lovers since she starred in the London

production of Evita, more than a decade ago. When the conversation turns to his turbulent

personal life, long a subject pursued with relentless enthusiasm by the drooling British press,

Rice vaults to his feet and begins to pace, leaving the sofa to his visitor.

Arrayed along the back of the sofa is Tim Rice’s career, neatly lined up in the form of small

needlepoint pillows, each bearing the logo of one of his shows. The big three: Superstar,

Joseph, and Evita, all composed by Lloyd Webber with lyrics by Rice. Each represents

the kind of success that creates modern fortunes; among the spoils is this house, which was

mentioned in the Domesday Book in 1086. This is the house that Superstar bought.

There is a pillow for Blondel, a disappointing show that ran in London but never made

it to New York. There is a pillow embroidered with an interesting disclaimer: "He’s my

boyfriend, lover, husband, friend—but he’s not my responsibility." Another pillow bears

a characteristically bitter lyric from Chess: "Is there no one in my life who does

not claim some right to steal my work, my success, my fame and my freedom?" And then there

is a pillow with the Chess logo itself, the rigorous black-and-white checkerboard pattern

belying the chaos evoked by the very name.

Chess has haunted Tim Rice for most of this decade. When the $6 million musical

finally opens in New York on April 28, it will end one of the most tempestuous, frustrating,

and disaster-prone journeys ever to carry a major show to the Broadway stage.

The saga of Chess begins in the death throes of the Rice-Lloyd Webber partnership in

the late 1970s. Lloyd Webber, a workaholic with a single-minded devotion to the musical theatre,

churns out scores at a pace few lyricists could keep up with. Rice couldn’t and didn’t

want to; distracted by more eclectic interests, he was far less enamored of the stage musical,

directing his passions toward outlets that range from rock music to book publishing to cricket.

Temperamental differences between the two men were exacerbated by competitiveness. Generally

diplomatic when discussing Lloyd Webber, Rice occasionally slips; he told one interviewer:

"Too much rivalry and egomania got in the way. He wanted to prove that he could do it

without me."

Then there was Rice’s affair with Paige, who starred in the London production of Superstar

as well as Evita and would also star in Chess. Lloyd Webber and his wife Sarah

(later dubbed Sarah I by the British papers) reportedly sided with Rice’s wife, Jane—a partnership

that was to rankle even more when Lloyd Webber subsequently fell in love with a chorus girl in

Cats and shed Sarah I and their two children in order to marry the saucer-eyed ingenue

with the Tammy Faye Bakker eyelashes, Sarah Brightman (Sarah II, who had divested herself of her

own first husband Andrew I—no kidding).

Meanwhile, Rice had this idea of writing a musical about chess, with an American grand master

and a Russian vying for the world championship against a Cold War backdrop of East-West intrigue.

Lloyd Webber wasn't particularly interested, so in 1981 Rice took his proposal to

Björn Ulvaeus and Benny Andersson, the songwriter-performers behind the Swedish rock

group ABBA. The band, which sold 250 million records during the decade it was active,

originally comprised two married couples (the women were the A's, Benny and Björn were

the B's). Their marriages hadn't survived international stardom either, and by the time

Rice came along the two men were looking for new frontiers.

As Scandinavians, they found the political resonance of Chess particularly appealing.

"Living in Sweden, you're very close to Russia," explains Ulvaeus (who has since

forsaken Sweden in favor of his own English country estate in Henley). "There are reports

every month of foreign submarines being detected; you feel the pressure the Russians exert

on Finland and sometimes Sweden; you feel how small and vulnerable you are, and how you have

to put up with this Big Brother neighbor who tries to force you to do certain things. It's

very real that you are in between."

It was 1983 by the time the new collaborators started to work in earnest on Chess.

Like Superstar and Evita, the project began as a rock opera that was initially

marketed as a record album, selling nearly two million copies worldwide and hitting the

charts on both sides of the Atlantic with two singles, "One Night in Bangkok" and

"I Know Him So Well" (a pop-gospel version of which became a hit for Whitney Houston

and her mother, Cissy).

Then came the task of turning Chess into a stage show. After conferring with

Trevor Nunn, who was so tightly booked they would have had to wait a year and a half for

his services, and Michael Bennett, the director of such Broadway sensations as A Chorus

Line and Dreamgirls, the Chess team signed up Bennett.

By Christmas of 1985 the director had completed casting, conceived the sets with designer

Robin Wagner, and ordered up a dazzling array of technology, including £1 million worth of

video equipment alone. Bennett envisioned a James Bond-style show with 128 television

monitors flying in and out to illustrate his concept of relentless, all-pervasive media hype

that can turn any event, let alone a politically charged international chess championship,

into a nightmarish circus. Having committed the show to a staggering budget, Bennett

stunned everyone by pulling out two weeks before rehearsals were to start for the London

production.

The British papers had a field day mongering rumors that the director had quit because

he didn’t like the book for Chess and because he had an unseemly fight with Elaine

Paige. What even Tim Rice didn’t know was that Bennett had learned he had AIDS.

Even now, nearly a year after Bennett finally succumbed to the fatal disease, Rice remains

bitter about having taken the rap for losing his director. "I didn't learn the truth

for a long time, and Elaine and I were getting blamed," says Rice. "All I wanted

was a denial that it had anything to do with the work, but when I tried to get some

confirmation that he was really ill, I was told by the Shuberts, 'lay off' I said, 'It is

allright for you, but I'm the one being attacked.'

In fact, Rice was the odd man out in a conspiracy of silence concocted by Bennett and

his most intimate advisers, including the heads of the Shubert Organization, Broadway's

biggest theatre owners and the co-producers of Chess. Faced with the need to

explain his withdrawal, Bennett and a handful of close friends cited a sudden,

mysterious case of heart disease, a lie they perpetrated in public and in private

virtually until his death. However, most of the collaborators on Chess knew

the truth; sworn to secrecy by Bennett, all concealed it from Rice.

"If somebody who's dying says to you, 'I don't want other people to know,' you

don't tell them, do you?" says one of the show's producers, Robert Fox, by way of

explanation. Bennett could easily have spared Rice with a statement that Chess was not

to blame for his default, but he didn't. Much as Bennett loathed and feared a voracious

press, its speculations served his purposes nicely, diverting attention from his own secret.

However, Rice's wounded pride was beside the point as the Chess consortium

confronted the prospect of seeing the whole enterprise go down the tubes, taking millions

of their dollars with it. Enter the infinitely clever, charming, and charismatic Trevor

Nunn, riding to the rescue like a dashing white knight-albeit one who demands a chunk of the

castle in return for saving it.

A bearded Svengali who parlayed his eighteen-year tenure as head of the esteemed Royal

Shakespeare Company into his current status as the Rambo of commercial theatre directors,

Nunn is renowned for being able to surmount any obstacle and emerge triumphant, whatever the

odds. He turns out transatlantic hits like Cats, Les Misérables, and Starlight

Express with the regularity of a metronome, thriving on a workload that would bring any

other man to his knees and racking up the dollars and the accolades like some insatiable machine.

Nunn's explanation of why he agreed to take on another director's half-finished production

and try to open it on schedule under terrible time pressure is thoughtful, considered, and

reflects exceedingly well on his largeness of spirit. "The Shuberts had been very

good to us when I was at the R.S.C., and I could see they were in terrible distress," he says.

"I also felt for Michael. I admired Michael to idolatry, and when I heard he had been

stricken with heart disease, which was the story at the time, I felt despair on his behalf.

So I undertook to do it. It's something that people in the theatre community can occasionally

do; you owe each other."

What Nunn does not mention is that in exchange for his services he extracted from the

Shubert Organization some significant concessions. In 1981 Nunn had won acclaim in New York for

his lavish nine-hour production of The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby (which,

like Les Misérables, was co-directed with John Caird), and now he wanted it

brought back for a national tour. The Shubert Organization reluctantly agreed-a decision

they would regret when Nickleby did poor business the second time around and they took

a financial bath on the venture.

Nevertheless, both they and everyone else associated with Chess were abjectly

grateful to Nunn for stepping in to save the day. The job he confronted was formidable,

and the task was further complicated when the computer that operated the whole technological

extravaganza broke down at a critical juncture during rehearsals.

Already revered for a talent that seemed equally able to illuminate Shakespeare, Dickens,

or the high-tech schlock of Starlight Express to best advantage, Nunn won even greater

admiration for the consummate professionalism with which he handled crisis after crisis on

Chess. "He seemed to me like a great R.A.F. pilot during the Second World War,"

says Robin Wagner. "His attitude was like Winston Churchill in a bombardment with rockets

blasting in your ear-very calm, cool, and collected in the middle of chaos."

Miraculously, Nunn did open Chess on schedule in London, where despite mixed reviews

it is still running two years later. But even its defenders agreed that the odd hybrid left

much to be desired.

"Trevor had to take over somebody else's concept, somebody else's design, somebody

else's casting, a whole production setup that wasn't his," explains Robert Fox, a dashing

blond Englishman. "Considering what it's been through, the show that's on in London is

remarkable, but it's not satisfactory in any way. It's a mishmash of styles and ideas."

Wagner adds with a grin, "We used to call it 'Nicholas Nickleby meets Dreamgirls.'

"

The collaborators immediately began to discuss changes for the New York production. If the

show's failings were subject to human correction, however, a key teammate was suddenly struck

with a baffling illness. The Shuberts, as they are known in the theatre community, are Bernard

Jacobs, president of the Shubert Organization and the partner most involved in both the artistic

and the negotiating aspects of theatre, and Gerald Schoenfeld, the chairman, who tends to deal

more with the organization's real-estate and public-relations concerns. Bernie Jacobs shared an

intense bond with Bennett; their friends describe it as a father-son relationship. To this

day, Jacobs will refer to Bennett, who died last July, in the present tense, then wince and

correct himself. Jacobs was devastated when Bennett learned he had AIDS, and both men dealt

with the news by resorting to a certain amount of denial. "Michael always believed he

was going to be the first one to beat it," Jacobs says softly. "For me it was very

hard to believe he even had it. I always looked upon Michael as somebody who was able to

sustain himself in the face of all kinds of adverse odds."

But as Bennett began to lose that final battle, Jacobs abruptly found himself facing a

bizarre ordeal of his own. One morning the seventy-one-year-old producer woke up and discovered

that, as he himself later put it, he didn't know where he was or how to find the bathroom.

The immensely powerful Jacobs, a man famed for his business acumen and his prodigious ability

to mastermind the most complex deals without forgetting even the most trivial detail, had lost

his memory.

This development threw his associates into turmoil. "It was awful," says Robert

Fox, grimacing even now at the recollection. "I was going crazy; I was here in London

in control of the organization of this thing, and I don't think Bernie would have known whether

he was seeing Chess or Kiss Me Kate at that point."

As time went on, Jacobs's impairment-described as "transient global amnesia"-

gradually began to improve, but there were more traumas to come. Nunn had brought in the

writer Richard Nelson to redo the book for Chess, seemingly an odd choice, but one

that met Nunn's requirements. Nelson is a highly political playwright whose works include the

didactic Principia Scriptoriae; he is an American; and he is not "somebody of

such worldwide fame that his signature was totally recognizable," as Nunn puts it.

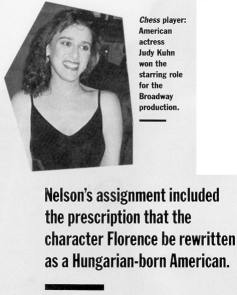

Nelson's assignment included the prescription that Florence-a Hungarian-born Englishwoman

who starts out as the American chess champion's second but then falls in love with the

Russian challenger-be rewritten as a Hungarian-born American. Rice agreed to this change,

realizing only after it was too late what a fatal error he had made; Elaine Paige is an

Englishwoman, and neither she nor anyone else thought she could get away with playing an

American on Broadway. The decision effectively cut Paige out of the New York production.

"If you're doing a piece aboout conflict and the chosen metaphor is East against

West-American's attitude toward Russia and Russia's attitude toward America-then in America

it seems to be an unnecessary complication if the main point of view through which you

perceive it all is a European one," says Nunn, smiling blandly. "We agreed it

would be better if the story had the essential Romeo-and-Juliet ingredient of lovers who

come from opposite sides."

This rationale, however logical, does not placate the enraged Rice. "The piece was

written for Elaine Paige," he says grimly. "It was not made clear to me that

the way Trevor Nunn wanted the show to go was to have Florence played by an American. I

don't know what his motives were, and I wish I had insisted Florence remain British-Hungarian,

instead of American-Hungarian. I let myself be overruled, which I bitterly regret. Trevor

had convinced everyone Florence had to be an American, and it's very difficult; you're put in

the position of 'He’s only doing it because it's his girlfriend.' That told against Elaine;

people don't like couples on projects."

Not that Tim Rice and Elaine Paige are your ordinary couple, although after years of coy

denials Rice has given up the pretense and acknowledged his double life. He lives part-time

with his wife and their two children at Romeyns Court, the manor house in Oxfordshire, and

spends the rest of his time with Paige at her Edwardian town house in London. Rice hastens

to assure one that relations with his wife are cordial: "We sort of lead separate lives

most of the time, but it's all very friendly," he says jovially. Jane Rice doesn't

always toe the party line, however; from time to time she erupts, informing the British press

at one point that she didn't know "what the hell is going on," that her husband

wouldn't talk about it, and that she had no idea what he did with his life in London. In the

last couple of years, the situation has been further enlivened by reports that Jane Rice was

being consoled by a handsome writer named Michael Stewart, who, when asked about their relationship,

offered helpfully, "I cannot deny or confirm reports that I am involved in a head-over-heels

affair with her."

"This whole marriage is full of question marks," Jane Rice complained.

Her husband, at least, has put the question marks to creative use in his work. Chess

revolves around an interlocking series of triangular conflicts. Florence is torn between the

American chess master and the Russian; when she chooses the Russian, he must face up to his own

obligations, weighing his love for Florence against his responsibilities to his Soviet wife

and children. The romantic triangles are echoed in the show's political construct; when the

Russian falls in love with Florence, he decides to defect, opting for freedom and passion

instead of the burdens and controls represented by his homeland. Needless to say, he finds

that such choices are not so simple.

"There is certainly a bit of an autobiographical thing in Chess," Rice

concedes disingenuously. "A man with two women pulling in different directions-yes,

well..."

Rice's ire over the rewrite on Chess was just beginning to subside when a new rumor

exacerbated the situation even further. Late last year gossip columnists in London and New

York suggested that Nunn was having an affair with the American actress Judy Kuhn, whom he had

just cast as Florence in Chess. Both Nunn and Kuhn, whose previous credits include

leading roles in Rags and the New York production of Les Misérables, vigorously

deny any romantic involvement. "Nonsensical, tacky, and ludicrous," Nunn scoffs.

Both London's Daily Mail and the New York Post printed retractions and apologies,

but the episode did nothing to improve Rice's humor.

Also galling was the knowledge that Lloyd Webber had succeeded where Rice had failed in

arranging for his lady-love's Broadway debut. During the years Rice has struggled with

Chess, Lloyd Webber has been almost obscenely successful; he currently has a total of

six productions-two each of Cats, Starlight Express and Phantom of the Opera-

running in the West End and on Broadway. Sarah Brightman starred in Phantom in London,

and the composer intended for his Galatea to come to New York as well. But Actors' Equity refused

to go along, insisting that the female lead be played by an American.

Lloyd Webber and the union argued to a standoff; then the composer played his trump card,

saying that if Equity didn't let his wife in, he wouldn't bring the show to New York at all.

Since Phantom had the largest advance ticket sale of any show in theatre history,

representing both a potential gold mine and many jobs, Equity caved in, and Brightman opened

on Broadway, albeit to decidedly unenthusiastic reviews.

Underlying personal rivalries also played a role in the final uproar that threatened to

derail Chess last December. As the holdiays began, the New York production seemed set.

"We had a script, new music, a cast, a plan, stuff going into the shops," recalls Nunn.

"I very carefully explained to everyone that I was going to be moving into a new house at

Christmastime. The house didn't have a phone, but there didn't seem to be any need for a telephone.

What happened next was a complete mystery to me."

Just before Christmas, Nunn-well known for his elusiveness under the best of circumstances-

slipped out of contact. Within days, everyone else began to panic.

The Shuberts were upset because they wanted Chess to open outside New York for a

pre-Broadway tryout, preferably at the National Theatre in Washington, which they manage.

That would have delayed the New York opening, and Nunn's schedule, as usual, didn't permit much

leeway; he was available only until mid-May, when he begins work on a film version of

Porgy and Bess. The Shuberts were also concerned about the financial structure

of Chess, fearing that costs were too high all around. Nobody could find Nunn

to work things out, and the day before New Year's Eve, the producers announced that Chess

had been postponed indefinitely due to "insurmountable scheduling difficulties."

With his usual combination of insouciance and malice, Rice says breezily, "It was partly

a stunt to find out where Trevor was. We thought, If we say we're not going to do it, Trevor

will surface-and he did. But he didn't let on where he was."

Even now, none of his colleagues knows for sure where Nunn was, a question made even

more mysterious by rumors, since denied, that he had just left his second wife (Sharon Lee-Hill,

a dancer from the London production of Cats). Nunn maintains he was at his new house

outside London, just where he said he'd be, but the prevailing opinion-and at least one

alleged sighting-had him in Australia, where he had just directed a production of Les

Misérables. What is known is that Nunn, who was furious, placed a conference

call to Tim Rice in Oxfordshire, Björn Ulvaeus in Henley, Robert Fox in London, Benny

Andersson in Stockholm, Bernie Jacobs on Shelter Island, and Gerry Schoenfeld and Tyler

Gatchell, the show's general manager, both in New York. With emotions running extremely

high, the global tangle of voices managed to thrash out a compromise; concessions were

made by all parties, and the show was reinstated. But when Nunn was asked where he was

calling from, he claimed the phone he was using didn't have the number on it.

Slipperiness is part of the Nunn mythology, of course. Bernie Jacobs drags a visitor

in to see his secretary; "Who's the hardest person to get on the phone, the most elusive,

the trickiest, most Machiavellian person we have ever tried to get in touch with?" he

demands. The secretary looks up, startled. "Are his initials T.N.?" she ventures?

As he wrote and sent new lyrics to Benny, Björn, and Trevor last winter, Tim Rice

took to sending along acid messages as well: "Would love to hear from you-and in certain

cases, of your existence," went one. Rice maintains he doesn't even have Nunn’s

telephone number. "I ring up his secretary, who lies and says she doesn't know

where he is," the lyricist says morosely.

Fox, on the other hand, says he has lots of phone numbers for Nunn. "They never

seem to answer," he muses. "Maybe they're just numbers given out to mollify me.

It's so frustrating, because by mid-afternoon the telephone is hot with calls from all

over: Where's Trevor? What's he doing? What's going on?"

What was going on during the last brouhaha was, as usual, more than met the eye. If

Chess had been delayed by an out-of-town tryout, it would not have arrived in New York

in time to meet the May 4 deadline for Tony Award nominations. That would have suited the

Shuberts just fine, since they were not eager to see Chess go up against the nine-hundred-

pound gorilla of shows, Phantom of the Opera, which had already swept Chess

aside in the London theatre awards.

However, others had personal reasons for wanting to compete with Phantom.

Fortified with a completely redone show with a new book, some new songs, a new concept,

and a new cast, Rice would relish competing head-to-head with Lloyd Webber. "I

would rather Chess won ten Tonys than Phantom, of course, but I won’t mind

half as much as Andrew will mind if he loses," Rice says mischievously. "Besides,

I've sold more records than he has."

Nunn may have a score of his own to settle. Lloyd Webber, for whom Nunn directed Cats

and Starlight Express, had initially considered giving him Phantom as well,

but then had chosen another director, Hal Prince. "Trevor wants to win the Tony and

take it away from Phantom and he believes he can do it," says one close

observer. "He wants to teach Andrew a lesson-particularly since Trevor and Hal

both want to direct Andrew's next show, Aspects of Love, and Andrew can't make up

his mind."

As it stands now, Chess will open on Broadway in time to compete with Phantom

at the Tony Awards. Since Chess is not the same show that was seen in London under

that title, the outcome is anybody's guess.

As rehearsals got under way in New York, all parties were on best behavior, trying not to

jeopardize the fragile peace in any way. Even for such a hardened array of theatre veterans

as these, however, the saga of Chess has been a bruising one.

"It's an amazing story," says Fox with a weary sigh. "Everyone has a

different view of why things happened or why people did what they did. Some will have

them to protect their own positions; some will have them to protect other people's

positions. I don't think the truth will ever be told. Because, after all, the truth is

only one person's view, isn't it?"

©1988 Vanity Fair

This article is reproduced for reference purposes only