LONDON (1978)

Cut to Prince's New York office, 1976, where Rice and Lloyd Webber stood, hats and record in hand. The album was good, they wanted him to stage

Evita and Prince said yes, but he wouldn't be free until 1978. Tim and Andrew decided Prince was worth it and they'd wait.

In the next year, the Evita concept album became a worldwide hit, selling two million copies. Tim and Andrew had no trouble this time raising money

for the stage production. Prince says the album's success caused problems: "All those people who listened to the concept album have a production of

Evita in their heads. But I'm not in their heads, I'm in mine. It's an interesting problem because you have to satisfy some expectations, yet

surprise them."

Julie Covington, who sang the role of Eva Peron on the concept album, was offered the lead on the stage. Rice remembers: "Julie Covington is a strange girl

in that she doesn't want to be successful. In that, she's been very successful. She turned down the part on the legitimate stage. She's a respected actress

in England but seems to be happiest doing very obscure and often very political plays." [Covington agreed to take over the role in Australia,

but dropped out at the very last minute. Stephanie Lawrence (who had done the role for months in London) flew in with her costumes and the show

opened on schedule.]

C.T. Wilkinson, the concept album's Che, was a rock singer with a steady recording and tour career. Though he had been in Superstar, he wasn't enamored of the musical stage either--at least not until ten years later when he began to use his first name, Colm, and created a sensation as the first Jean Valjean in the musical, Les Miserables.

There was a "world-wide casting call" for an unknown to play Eva Peron that was publicized as if it was the search for Scarlett O'Hara, but Prince, Rice and

Lloyd Webber eventually chose Elaine Paige, a tiny bundle of energy with a giant voice. She had played small roles in Superstar, Billy

(with Michael Crawford), Grease and Hair. David Essex, who was given first billing, had played Jesus in Godspell, but was best-known

for his recording and concert work, as well as his own TV show. To round out the triumvirate, highly respected classical actor Joss Ackland would play Juan Peron.

Prince worked with the authors to make the transition from record studio to stage. He had the music re-orchestrated to make it more of a musical theatre style

and to remove the more blatant rock elements which would date the piece. There were small changes throughout, and one song was deleted, "The Lady's Got

Potential," which was all about Che inventing an insecticide(!) and Peron learning to ski in Italy:

Just one blast and insects fall like flies!

Kapow! Die!

They don't have a chance

In the fly-killing world

It's a major advance

In my world

It'll mean finance

I'm shaping up successful capitalist-wise

There were other references to Che and his bug-spray elsewhere in the show:

Forgive my intrusion but here in this neat little can

I have a product to change your conception of man

A brand new insecticide a remarkable chemical feat

Instantly rendering other insecticides obsolete

Prince wisely tossed out this whole subplot (the song--with new lyrics--eventually resurfaced in the film) and made Che's anti-Peronist stance more ideological than personal. The old song was replaced by "The Art of the Possible," which became one of Prince's greatest staging coups--Perón rising to power via a game of musical rocking chairs.

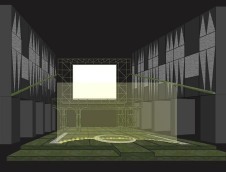

Prince hired Timothy O'Brien and Tazeena Firth to design the show. After their first meeting with Prince in 1977, they didn't know where to begin. "We

went away from that meeting in Majorca saying 'How on earth are we going to do justice to this piece?' It seems so simple now--but then we had two records.

That's all."

Since Evita begins with a scene in a cinema in Buenos Aires, they were saddled with what they called an "obligatory cinema screen." Then they realized "it

could become an active principal on stage and might inhabit more than one position on the stage." Impressive in size (34 by 23 feet), the screen is attached

to the mirrored side walls and moves from a low downstage position to a high upstage one. Its motion is majestic, heightened by a bank of lights set into

its base which shine directly downward cutting a brilliant swath across the stage whenever it moves. "The first time it moved in England," says O'Brien,

"it was like a giant battleship slipping in its moorings and sliding downstream on the tide."

They also decided on a raked stage for a more effective presentation of the actors. Into it, they embedded a circle, a larger semi-circle and two parallel

lines of light. Hal Prince described them to the company on the first day of rehearsals in London: "There is a semi-circle here, which is a light curtain.

Sometimes there will be nothing on the stage but performers and that light curtain. If you step through it, you come from nowhere. If you step through it

the other way, you disappear before the audience's eyes."

Prince was happy with their design but knew something was missing. His biggest challenge in Evita came in trying to create the illusion of the

millions of people Eva and Juan Peron called their descamisados. Then the director and designers recalled Mexico's Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente

Orozco murals and they had their answer. The theatre's side walls, ceiling and stage would be draped with huge painted canvasses (see

The Set section) bulging with the people of Argentina. Prince said, "if you're in the fourth row of the stalls, you're in it---actually under this mural.

Everything about this will focus you in, pull you in from the rear row of the stalls right into this environment."

Prince was happy with their design but knew something was missing. His biggest challenge in Evita came in trying to create the illusion of the

millions of people Eva and Juan Peron called their descamisados. Then the director and designers recalled Mexico's Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente

Orozco murals and they had their answer. The theatre's side walls, ceiling and stage would be draped with huge painted canvasses (see

The Set section) bulging with the people of Argentina. Prince said, "if you're in the fourth row of the stalls, you're in it---actually under this mural.

Everything about this will focus you in, pull you in from the rear row of the stalls right into this environment."

As noted above, Prince wanted Che specifically identifiable as the revolutionary Guevara. To explain his presence in Evita, Rice added a verse to

Che's opening song:

Who am I, who dares to keep

His head held high while millions weep

Why the exception to the rule?

Opportunist, traitor, fool?

Or just a man who grew and saw

From seventeen to twenty-four

His country bled and crucified

She's not the only one who's died!

One Los Angeles critic suggested that Walter Mondale or Abbie Hoffman would do just as well as an opposition figure, but Guevara was at least born in Argentina

and was there during Eva's reign.

Best remembered for his vital part in Castro's takeover and initial administration of Cuba, Guevara became a legend when he was killed while fighting in

Bolivia in 1967. Born to radicals of aristocratic heritage in Rosario in 1928, Che enrolled in medical school at the University of Buenos Aires in 1947.

Though there were many student anti-peronista groups, he seems not to have participated in any of them.

People's lives rarely provide the suspense of original drama, and Che's presence in Evita contributes that sort of suspense. The actual opposition to the

Perons came from many splintered factions and was often lacking articulation and leadership. When a leader emerged who showed signs of developing a

following, he was quickly deported to Uruguay.

The British press greeted Evita's theatrical launching with such hysteria that it nearly forced the production team into seclusion. The staid Sunday Times put Elaine Paige on the cover of their color magazine in a replica of the Argentine stamps bearing Eva's profile. Dewynters, the undisputed top theatrical design firm, created a memorable logo by superimposing Eva's head on the Argentine flag.

The country's flag actually does not contain the sun, only the Buenos Aires province flag does, but as the only major city in Argentina, it is the most common

flag seen. The first poster was originally in Argentine blue and white on black, but the eventual black and silver logo identifiable all over the world probably

came about from the set design--the sidewalls are black and mirrored points--very like the sun points over Eva's head.

The country's flag actually does not contain the sun, only the Buenos Aires province flag does, but as the only major city in Argentina, it is the most common

flag seen. The first poster was originally in Argentine blue and white on black, but the eventual black and silver logo identifiable all over the world probably

came about from the set design--the sidewalls are black and mirrored points--very like the sun points over Eva's head.

It's hard to remember that Evita was the first show to create such avid anticipation long before opening night. Now that Cameron Mackintosh has honed and

refined this art of orchestrated hype for shows such as Les Miserables, Miss Saigon, The Phantom of the Opera and Cats, it's become the

standard.

Nothing about Evita happened quietly. This was partly due to its controversial subject, but mostly because Robert Stigwood, who produced Evita

with his theatrically savvy associate David Land, already had a massive publicity machine in place, used for his promotion of rock groups like the BeeGees

who were under contract to his RSO Records. When Evita opened at the Prince Edward Theatre, it was reviewed as far away as Singapore, India and

Sweden.

"After the ludicrous ballyhoo, there was a danger the show itself would be an anti-climax," The Guardian's Michael Billington said after Evita's

premiere on July 21, 1978. "But the first thing to be said about Evita is that it is an audacious and fascinating musical."

"Evita is a superb musical, but its heart is rotten. It is a glittering homage to a monster," huffed critic John Peter in The Times. "I never cease to marvel at the sentimental fascination English people feel for political cannibals. Watching Evita is, in some ways, like looking at shop-windows selling Nazi uniforms and Japanese bayonets; they seem to cast a baleful spell on the curious innocents who never saw them in action."

Rice's contribution was generally discussed more in terms of the "book" [Rice insists there is no book, though he won a Tony Award for it] or idea, rather than his lyrics. The Times's music critic, Derek Jewell, knew the difference. "Everything is sung in Evita. No lumbering book links it, but elegant and powerful recitative which continually points up character... practically every word of Rice's can be instantly savored by the audience ....in Tim Rice, Andrew has a partner of perfection. Rice writes trenchant, modern lyrics, superbly married to Lloyd Webber's ambitious score."

The Times' critic Bernard Levin incites Rice's wrath to this day: "Bernard Levin accused us of bringing about the downfall of the century. He thought we were responsible single-handedly--or double-handedly--for the decline of civilization since about 1945, which I think was a little over the top. Evita isn't a perfect work, but I think his criticism was a little heavy. [Rice got his revenge during his speech at the Prince Edward on Evita's closing night a long seven years later. His final remark was "Bernard Levin, f---- you!"] You tend to get much worse reviews if you have a hit. You either get raves or absolutely dire reviews. With Evita we've had both."

Oddly enough, it seems that on later reflection, most critics revised their opinions of the show and the quality of Tim's lyrics. Critics in London, Los

Angeles and New York all voted for Evita for various awards, despite having panned the show just a few months earlier. Frank Rich, the longtime

New York Times theatre critic and dreaded "Butcher of Broadway," had quite a change of heart about Evita over the years. Reviewing the

London premiere, Rich said: "Evita's London success far outstrips the show's merits...[it] is a cold and uninvolving show that does little to expand

the traditional musical comedy format or our understanding of a bizarre historical figure...we have no idea how to judge her; to Rice, fascism seems to be

more a cultural style than a political ideology...if Rice were a dazzling writer, such silliness might be tolerable, but his lyrics rarely rise above the

cute. The show's structure is clumsy."

By 1988, Rich had mellowed considerably: "Throughout his career [Andrew Lloyd Webber] has been held hostage by his lyricists. If a composer is working with

unsophisticated lyrics, he's in trouble. The most sophisticated lyricist, in my view of Lloyd Webber's career, has been Tim Rice. While Evita

may in some ways be a naive and simplistic historical view of the Perons, as show business lyric writing, Rice's work is very clever and I think Lloyd

Webber responded with a more interesting and varied score than usual."

In later books on musical theatre, Rice is usually lauded, particularly for his work on Evita. Sheridan Morley cited two lyrics:

Show business kept us all alive

Since 17 October 1945

and:

They need to adore me

So Christian Dior me

as "the kind of lyrics Porter or Coward could have envied." In his mammoth two-volume history of the British musical theatre, Kurt Ganzl says, "Although some critics condemned Evita for what it was not, the public had no such qualms. Here they had been presented with what was undoubtedly the best piece yet in the modern musical style: an unsurpassed blend of writing and staging, well performed and played in an idiom in which only the same authors' Jesus Christ Superstar provided any real comparison. The show instantly became the hit of London, its balcony scene with the white-garbed Evita, arms aloft, burning itself into memory as one of the abiding musical theatre images of modern times. "

With that image, Elaine Paige became an instant star after opening night. The praise was unanimous: "Elaine Paige's transformation in the role is one of the rewards of the evening: starting as a dumpy, mouse-haired little scold, acquiring the sumptuously voluptuous looks of a pampered courtesan...she handles the changes with shocking immediacy, and her voice fills the theatre like a whole brass section; most expressive of all is the extent to which she shows Evita becoming totally captivated by her own dream, " said Irving Wardle of The Times. Other headlines summed up: "Don't cry for Elaine, she's an instant superstar;" "Little Elaine, you're great;" "Elaine takes town by storm;" and "A star is born."

This commentary is actually continuous, though relevant parts have been placed under each production's section. To read the entire commentary straight through, use the buttons below:

This material is strictly the opinion of the author of this website.

© 2000

|