BROADWAY (1979)

THE TRYOUT

American audiences were not as well-informed or well-prepared for Evita's arrival. The concept album hadn't done well in the U.S. because it didn't

fit into established radio station formats and got no airplay. But the cast was well prepared. On the first day of rehearsals in New York Hal Prince

established a modus operandi he would use for every company of Evita he directed: he showed documentary films of Eva and Juan Perón doing their

stuff on the balcony of the Casa Rosada.

The three leads hired for New York all had years of experience but were virtually unknown. Patti LuPone was a veteran of Julliard and John Houseman's

famed Acting Company. Mandy Patinkin was an avant garde actor who, like Julie Covington, had been in a lot of obscure political plays and nobody knew he

could sing. Bob Gunton, who received a Tony nomination for his intricate portrayal of Peron, recalls his audition. "I originally wanted to play Che. I

didn't think I had a chance, but I did want to audition for the role and I even began growing the beard. I went up to Hal's office with my beard and looking

a little funky and the casting director handed me the sides and it said 'Peron.'"

Instead of opening cold in New York, the production team decided to take advantage of the huge subscription base the Los Angeles Civic Light Opera had at

that time in L.A. and San Francisco. The luxury of a pre-paid, guaranteed audience for a 15-week pre-Broadway tryout was too good to pass up. Tim had

to do a few rewrites to get the most obvious Britishisms out: "There were lines like 'get stuffed'--one of my more memorable lyrics--that line had to go

because it doesn't mean much in America, so that became 'up yours.' But of course, if you change 'get stuffed' to 'up yours,' then you've got a rhyme

with 'stuffed' that also has to change, so I had to change the whole verse. It's like a deck of cards; you pull out one rhyme and eight other rhymes

collapse.

Several minutes were cut from the final scene with Eva and Juan where she begs to become vice president. The trimming helped the flow, but lost us one

of Rice's more wrenching lyrics for Eva [or was it just Covington's splendid delivery?]: "This is not a gambler's final throw." The removal of the second

verse of Eva's "Lament" caused some confusion. The final verse was originally:

The choice was mine and no one else's

I could have the millions at my feet

Give my life to people I might never meet

Or else to children of my own

Remember I was very young then

Thought I needed the numbers on my side

Thought the more that loved me the more loved I'd be

But such things cannot be multiplied

However, Eva's last words before her death were left in:

Oh my daughter! Oh my son!

Understand what I have done!

Without the explanation of the verse quoted above, some members of the audience thought it meant that Juan and Eva had children, not that she was referring

to her own sacrifice. Bob Gunton said there was also a moment where at least one person thought she saw those children: "I was interviewed by a woman

for a conservative Catholic monthly. She was a bright, but very conventional lady, and very nice. She was under the impression that during the 'Rainbow

Tour' number, those two little girls on my knees were their children that Peron was looking after while Eva was away in Europe. I guess I'm not being

blatant enough, but it seems to me that these two nubile chickies sitting on a dirty old man's lap--I sit there staring at one girl's breasts for one

whole verse--well...."

Rice didn't feel the opening in Los Angeles in May 1979 was particularly auspicious: "On the opening night, there was absolutely no petrol in California,

[referring to the energy crisis which had Angelenos lining up for hours at gas stations every other day, according to their license plate numbers]. The

show went pretty well; the reviews were excellent, which was surprising because I didn't think the opening night was all that wonderful. By the eighth

night, it was simply smashing. We had several built-in disadvantages. The place that it opened in was a huge barn which sat 3,400 people, which is about

three times as many as the London theatre. So everybody had to really yell into the microphones and that sort of upset the balance of the piece."

Rice didn't feel the opening in Los Angeles in May 1979 was particularly auspicious: "On the opening night, there was absolutely no petrol in California,

[referring to the energy crisis which had Angelenos lining up for hours at gas stations every other day, according to their license plate numbers]. The

show went pretty well; the reviews were excellent, which was surprising because I didn't think the opening night was all that wonderful. By the eighth

night, it was simply smashing. We had several built-in disadvantages. The place that it opened in was a huge barn which sat 3,400 people, which is about

three times as many as the London theatre. So everybody had to really yell into the microphones and that sort of upset the balance of the piece."

The Los Angeles audiences were--at best--confused about just who Eva Peron was. Before he heard the documentary in 1973, Rice said all he knew about Eva was

that she was on stamps and was dead. Angelinos didn't even know that. Arguments erupted during intermission and after the show in the lobby among audience

members, many insisting the piece was fiction. After all, if this woman was so powerful, why had they never heard of her? Los Angeles magazine's

critic headlined his review, "Eva Who?" Another critic complained that the show wasn't factual because Juan Peron's wife survived him to become

president--confusing Eva with Isabel, Peron's third wife. Misconceptions, mistakes and mis-identities plagued the early reviews.

Then there were rumors of backstage trouble. Patti LuPone's reviews were less than ecstatic: "As Evita, Patti LuPone looks the part, acts it well, but

can't quite cope with its vocal demands;" and "Although Patti LuPone is the star of record, it is Mandy Patinkin, as the narrator and opposition, Che,

who wrests control of the stage...and more of a problem, her diction is not always precise enough to put over the tricky lyrics...what operas like

Evita need are new kinds of performers--actors and dancers who can sing as well as the average Met chorister."

Shortly after the opening, Barbra Streisand contacted Robert Stigwood and offered to buy the film rights to the show. He declined, knowing they'd be worth

much more later, and that should have been that. But the rumor mill sniffed out the meeting and it was followed by press reports that Stigwood,

Prince & Co. were unhappy with LuPone and were trying to talk Streisand into taking over the role. Prince's notorious habit of disappearing for weeks at a time only fanned the flames. His absence only made it harder for Patti.

As Rice noted, the theatre was huge. Bitter performers have dubbed the 3,197-seat Dorothy Buffum Chandler Pavilion at the Los Angeles Music Center "Buffy's

Cavern" and it is intimidating. Body mikes were relatively new to the musical theatre then and Patti was used to projecting her voice to fill whatever space

she was in." Patti said, "I really should have had three months of opera training. This kind of singing was brand new and no one knew what it took to do

it. They forgot that Elaine lost her voice after the first month in London. I also had to inherit all of Elaine's costumes and choreography. I had to

learn it all and then unlearn it, because it didn't work for me. At first Hal had me doing this ridiculous motion with my arms in 'Buenos Aires,' chugging

along like a damn train."

She also had difficulties maintaining the integrity of her characterization as post-opening wig, costume and movement changes were made. The problem was

simple: Patti wasn't a dancer while Elaine was, and their physical and vocal styles were quite different.

Evita was the first of the mega-musicals to be cloned all over the world, each version identical to the last. Prior to this time, it was usual for a

Broadway company to close in New York and then go on the road. Sometimes the principals would go to London a year later and do the show for three months.

A really big hit might spawn a second company but it was rare.

However, Stigwood and Prince had the future of Evita all mapped out. Even before the Broadway opening, sets were being built for a second U.S.

company and plans were ready for Japan and Australia. In this inexorable assembly line that has now become the norm, directors rarely have the time or

inspiration to redirect each company to capitalize on individual performer's strengths. Other than rethinking the role for Patti and (taking into

consideration future Evas) the only real exception Prince ever allowed in any of his Evita companies was for Marti Webb in London. She was

by far the best-known actress to play the part for some years, she insisted that "her" Eva would not cry real--or fake--tears on the balcony. Hal

let her do it differently because, she was a respected stage actress and singer, plus she agreed to play Eva for a month while Elaine was on holiday,

be the alternate for another six months and then take over the part.

Another first was the use of alternate performers for the lead role. This is now commonplace on Broadway and the West End, where alternates take over

starring roles in several performances a week in Phantom, Miss Saigon, and other big shows. After losing her voice, Elaine got an alternate in

London who did two performances per week, and the same schedule was dictated for all future companies. But in every company, having two women lusting to

go on is tricky. Those that do six insist they can do eight; those that do two guiltily hope for the other's vacation or indisposition so they can do

it every night.

Patti's alternate, Terri Klausner, had been reviewed several weeks after the L. A. opening and got the raves that Patti hadn't. "[Terri Klausner] has

a sharper, more tensile vocal quality that gives the production a great deal more theatrical definition" and "She is grasping as Eva Duarte in her climb,

authoritative as Eva Peron in her prime, poignant as Evita faced with her immortality, and even engenders empathy [at the end]."

As the weeks passed, Patti lived with the pressure of the pre-Broadway engagement, the strain of recording the cast album during the day, performing at night and reading everywhere that she was about to be dumped. And the ultimate crushing blow to any star's morale: Mandy Patinkin regularly got much heavier applause than Patti at the curtain calls. It all came to a head on closing night in Los Angeles.

From the moment Patti sang her first note, it was clear something was very wrong. She didn't sing the choruses of "Good Night and Thank You," and though

the other actors and conductor Rene Weigert helped her in every way they could, by the time she got to "A New Argentina," she could not even speak the

lyrics, let alone sing them.

In the theatre, the intermission stretched on and on, the audience knew what the problem was and they were speculating on how it would be solved.

Terri Klausner would have to finish the show, but her makeup, wigs and costumes had been packed and loaded onto the trucks right after that

afternoon's matinee for the show's move that night to San Francisco. 'Backstage was chaos during intermission,' said makeup and hairstylist Richard Allen,

'Patti in tears, Terri not in makeup, her costumes and wigs were all over the trucks, had been put there after her matinee, and we had to get it all out,

and on her. We almost missed her entrance.'

Finally an announcement was made: "Ladies and gentlemen, the management regrets that due to illness, Patti LuPone will be unable to complete this evening's

performance. Terri Klausner, who has played the role of Evita at all Los Angeles matinees to critical acclaim, will perform Act Two." Terri got a rousing

hand on her first entrance and gave the performance of her life. She did the role more in Patti's style than usual, but Patti was devastated: "It was

closing night and a lot of my friends were there. A lot of people were coming back to see the show and a lot of Evita fans. A wonderful thing

was going to happen at the curtain call [a parade of ushers with red roses] and I woke up that day and I knew my voice was peculiar. I didn't want to

think about it...Mandy said I shouldn't go on, but I said, I have to go on. By the end of 'A New Argentina,' I couldn't hit any notes whatsoever. I

couldn't finish the show, so Terri Klausner went on and finished. And, while I was sobbing in the dressing room, packing my makeup, having failed, I

thought, now this is theatre. The audience gets to see two Evitas. It's something they certainly didn't expect." Many members of the audience left

the theatre with flowers, obviously intended for Patti, still in their hands. Backstage, the mood was very down, as if the triumph of the past months

had faded.

Patti disappeared the weekend the show was trucked up to Northern California and worried a lot of people, but she just needed some time alone and was

back at work the first day in San Francisco. By the end of that week, she was still hoarse for the opening and again, her reviews were mixed. Hal

Prince materialized, reassured the company that he was happy with most everyone and everything--especially Patti--and then took off again for Majorca.

Patti was furious that he was incommunicado when she felt she needed him during the San Francisco run, but Bob Gunton understood the director's tactics:

"We've been directed in three segments--the initial period, the mid-stroke stuff in L.A. and the opening here. The show doesn't yet have the wattage it

will have because we haven't gotten Hal's final gunshot yet. His method is painful to some people, because he gets everyone nervy-jumpy, but his shows

always have great openings."

The rumors continued; someone kept removing Patti's good notices from the bulletin board backstage at the Orpheum and replacing them with Terri's, and then

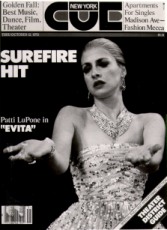

Cue magazine featured Patti as Eva on their cover with the headline, "Surefire Hit." This set the New York critics' teeth on edge and put even more

pressure on Patti, who was feeling the weight of the entire mega-musical rested solely on her shoulders, "The show isn't called Che, is it?!" The

hype was building all over town. The San Francisco CLO even had table tents with the show's logo in bars around town advertising a new Evita

cocktail (Midori Melon Liqueur, Suntory vodka, lemon and orange juice).

The rumors continued; someone kept removing Patti's good notices from the bulletin board backstage at the Orpheum and replacing them with Terri's, and then

Cue magazine featured Patti as Eva on their cover with the headline, "Surefire Hit." This set the New York critics' teeth on edge and put even more

pressure on Patti, who was feeling the weight of the entire mega-musical rested solely on her shoulders, "The show isn't called Che, is it?!" The

hype was building all over town. The San Francisco CLO even had table tents with the show's logo in bars around town advertising a new Evita

cocktail (Midori Melon Liqueur, Suntory vodka, lemon and orange juice).

Just as the gay community in Amsterdam had been a catalyst helping get the first Superstar single noticed in Europe, so the gay community in

San Francisco adopted Evita and Patti LuPone. The Advocate and After Dark both ran multi-page stories on the show and in-depth

interviews with Patti. As her performances gained assurance and became more and more riveting, the gay community flocked to the show. They loved it

and soon all San Francisco loved it. Their encouragement in the theatre every night helped Patti gain complete command of the role. By closing night

in San Francisco, she was finally the star of the show.

During the Bay Area run, a performance almost had to be cancelled. The company spent their day off filming two 30-second TV commercials and the clear

plexiglass pieces over the recessed lights in the stage melted and buckled from the lights under them being on for fourteen hours straight. The stage

looked like a war as seen by Salvador Dali, with twisted plexiglass sticking up all over the place, and a performance the next night looked impossible.

The production crew scrambled and the identical pieces already completed for the second company's set were flown out from New York.

NEW YORK

The star and her show had a triumphant opening night at the Broadway Theatre in New York on September 21 and a typically lavish bash afterwards at the trendy

Xenon nightclub (the Stigwood Organization is known for its fabulous parties), which played a new Evita disco album all night. That isn't to say the

show got raves. The reviews were decidedly negative (though these same critics would vote Evita "Best Musical" several months later). Walter Kerr (New

York Times) said that the audience only heard about the most dramatic events, never witnessing them, and that the show "puts us into the kind of

emotional limbo we inhabit when we're just back from the dentist but the novocain hasn't worn off yet."

John Simon (New York) flung flaming arrows at Evita: "Stench is stench on any scale...if you want to help fill the coffers of these two amoral,

barely talented whippersnappers [Rice and Lloyd Webber] and their knowing or duped accomplices, by all means see this artfully produced monument to human

indecency. The bad taste of the offering should linger in your mouth." Variety liked it better, saying it had "inventive staging, plenty of

movement, and a score interwoven with lyrics that continuously accelerate the story," and The Hollywood Reporter called it a "big, exciting

show whose theatricality is written in boldface."

But in the end, the reviews didn't matter. Audiences flocked to the show and it was sold out for the first two years. It was everything the hype had said it was.

A synopsis of Eva Peron's life had been added to the playbill in San Francisco and New York and the pre-opening hype made sure New Yorkers knew who the Perons were.

The TV commercials were little playlets of their own. In them, Patti LuPone appears as both a young, scrappy Eva and in the glittering white dress. The announcer urges you to see "Evita--Argentina's instant queen and overnight saint--and only a few seemed to notice she simply seduced a country." The TV commercials ran so incessantly, they were parodied on SCTV as "Indira" and "Stand Back Rawalpandi." Forbidden Broadway--now an established Off-Broadway satire show--was then a feisty group in a tiny nightclub. But they had heard the rumors out on the coast too, and Broadway insiders howled when Nora Mae Lyng aped Patti LuPone and sang:

Don't cry for me, Barbra Streisand

The truth is I never liked you

You'll do the movie, and what a bummer

When you sing Eva like Donna Summer

Many of Tim Rice's words have entered into the language; not just 'Don't Cry for Me,' but I've seen articles headed 'Dangerous Jade' and the Los Angeles Herald Examiner banner headline on the day the Falkland War started was "Stand Back, Buenos Aires," and ran an editorial cartoon in the style of the Evas with their arms raised, only this time it was a skeleton and the words in the disctinctive Evita font were 'GUERRA.'

Tim Rice gained fame with Jesus Christ Superstar; he gained respect with Evita. But a lot of things were changing in both his and Andrew's lives, and the minor annoyances of the past now became big stumbling blocks. As Evita opened around the world, Lloyd Webber was seldom there; if he was, he came in a few days before opening to work with the orchestra and left before the big night. Rice was left to do the round of publicity and interviews alone. They occasionally talked of future projects together but the truth was that the partnership which lifted the British musical out of its doldrums was no more.

This commentary is actually continuous, though relevant parts have been placed under each production's section. To read the entire commentary straight through, use the buttons below:

This material is strictly the opinion of the author of this website.

© 2000

|