I'm only a radio star with just one weekly show

But speaking as one of the people I want you to know

We are tired of the decline of

Argentina with no sign of

A government able to give us the things we deserve

--Evita

Wonderful Town

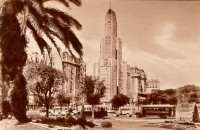

Even today, when the media is able to catapult unknowns into the spotlight overnight and plunge them into obscurity with equal ease, Eva’s ten-year ascent from impoverished schoolgirl to first lady of Argentina is stunning.

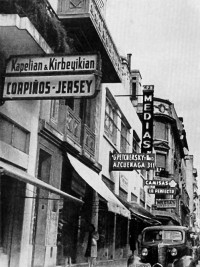

In the mid-1930s, the young women of the unskilled working class in Argentina frequently turned to prostitution as the only means of supporting themselves. They were confined by the rigid social structure, lack of education or connections. Others worked in shops, factories and as sales clerks, but these jobs paid so little, prostitution was an attractive alternative.

There were over 200 official houses of prostitution in 1934 Buenos Aires, but these girls were forced to attend over 80 clients per day, so many found it easier (and more profitable) to go into business for themselves. Eva’s detractors have always maintained that she became one of these girls upon her arrival in Buenos Aires, but there is no evidence that she did so.

Arriving in January, Eva managed to get small parts in stage productions in March, July and November of 1935. As any actress can attest, days of walking, hours of waiting for a seconds-long interview or audition, and sheer stamina are required to get any part, however small. These factors increase a thousand-fold if you are inexperienced and untrained. Eva was frail, sickly and thin; it is hardly possible that she could have presented an appealing front to potential brothel customers by the time evening arrived.

In 1936, Eva got about as much work as the year before, and the parts were no larger. She did get her photo in a magazine, though, and then was hired by a repertory troupe which did plays in the provinces and even went to Montevideo, Uruguay. When she returned to Buenos Aires, she sought out the troupe leader, Pablo Suerro, because he was casting a new production. But he humilliated and degraded her in front of a lobby full of people, yelling that neither her sexual nor her acting talents were needed.

Eva then entered into a long-term relationship with a young actor and it seemed for a while that they would get married. But he behaved in a typically Argentine fashion and left Eva to marry a "respectable" girl. Men at the time rarely married their mistresses and Eva hadn’t yet learned how to make herself a truly valuable companion and asset.

Her third year in the capital city improved after these setbacks. Eva began to meet more influential people and made friends with several who took an interest in her career and helped her in many ways. After the debacle with Suero, she could get nothing until March when she was cast in Pirandello’s La nueva colonia ("The New Colony") at the Teatro Politeama. It didn’t run for long, but an early contact paid off when Eva met Mauricio Rubenstein of Sintonia magazine through Agustín Magaldi. Rubenstein was an editor of this fan magazine and he in turn introduced her to Emilio Kartulowicz, the publisher. She hung around the office waiting for him and watched him at car races, and their names were linked together. Their relationship, whatever its nature, paid off when Kartulowicz recommended her for a small film part (her name isn’t even listed in the credits) in a boxing comedy, Segundos afuera ("Seconds Out!"). It wasn’t much, but it paid the rent and kept her working for several weeks. If it is possible to believe the fan-magazine puff piece, Eva and the star, Pedro Quartucci, had a brief romance during the promotion for the film, and a number of racy photos of the two of them appeared in the press.

It was again several months before her next job; meanwhile, she pounded the pavement and starved. Finally, Rafael Firtuoso, impresario of the Teatro Liceo, gave Eva a five-month contract with his company of actors. Though she only had a non-speaking part in ¡No hay suegra como la mía! ("There’s No Mother-in-Law Like Mine!"), its star, Pierina Dealessi, saw some potential in Eva’s frightened eyes and made something of a pet out of her, giving her advice about clothes, how to move on a stage and how to improve her diction.

Eva had plenty of competition for these small parts, but she was so determined, so relentless, that those who knew her at this time say they recognized a special quality in this girl who made such an effort to be interesting and friendly. "She lived in a pensione that was very poor, very humble," said Dealessi, "so she came very early to the theatre...after a performance or a rehearsal, her brother Juancito would be patiently waiting for her outside." Eva did two more plays at the Liceo in 1938, one in March and one in July. She also worked as model for clothing stores and hair salons, and did a promotional film for a soap company.

If Eva had ever been really close to Agustín Magaldi, she lost another person she cared about that year when he disappeared under mysterious circumstances. Whatever the reason, after this time, it seemed that the friendships Eva made were never as deep and the romances never seemed to touch her heart as they did before. She withdrew and turned inward, projecting a mysterious and distant quality that men would comment on for the rest of her life.

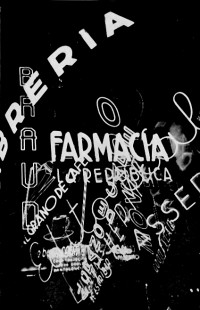

Eva’s last appearance on the stage was at the Teatro Astral in Mercado de amor en Argelia ("Marketplace of Love in Algeria") in January 1939. The play ran for more than 100 performances, a rarity in Buenos Aires. It wasn’t a big success for Eva because she was still a bit player. But her mentor Emilio Kartulowicz then took her from the stage, which wasn't moved by her talent, to the thriving medium of radio, which was.

Radio Prieto agreed to star Eva and Pascual Pellicciota (one of Pierina Dealessi’s co-stars at the Liceo) in a series of historical dramas of Argentine life. The first program, Los jazmines del ochenta ("The Jasmines of the Eighties"), premiered on May 1, and the installments continued through the end of September. Eva jumped the gun a little on her star status, renting an apartment at the Savoy Hotel, which she had to give up within weeks. She moved back to a tenement in the Corrientes area, but she had still managed to make forward progress. In April, she appeared on the cover of Antena, a weekly radio program guide bought all over Argentina for its listings. The popularity of her dramatic series may not have made her a household name, but she appeared regularly in the fan magazines and tabloids now, and got a part in another film at the end of 1939, La carga de los valientes ("The Charge of the Brave Men"), produced by Pampa Films.

Eva turned herself into a young woman who was pretty, cooperative and photogenic, so she was used for promotions for her film and radio work that far exceeded the size of her parts. Fan magazines gave her a completely phony middle-class past, credited her with many romances and cultural taste far beyond what she had ever been exposed to. There is little doubt that Eva longed to be a film star; it was the wish fulfillment of her earliest girlhood dreams, but her natural talent worked better on the radio than it did in any other entertainment medium, though it was over a year before she accepted and then capitalized on this talent.

Shortly after the premiere of La carga de los valientes, Eva turned 21 and then started another film, El más infeliz del pueblo ("The Unhappiest Man in Town"), for EFA Productions. She also auditioned for several notable directors who were part of the stream of European filmmakers migrating from war-torn Europe. She did some spot work on the radio and starred in another drama, Los amores de Shubert ("Shubert’s Loves"), for Radio Prieto. Eva landed the most important of her film roles to date in Una novia en apuros ("Sweetheart in Trouble") for a North American director, John Reinhardt.

People had noticed Eva’s broadcasting flair, though, and the Gureño brothers, makers of Radical Soap, signed Eva to an exclusive contract. They also employed her brother Juan as a broker for their products, and this may have been the means of Eva’s big break. She formed a company with Pablo Raciopi (her co-star from the previous year’s historical dramas) called Candilejas ("Footlights") and they developed a soap opera program which was done at Radio El Mundo. It was only a short time before Eva was also doing a morning show, Amancer ("Sunrise") at Radio Argentina.

Eva finally had the security she’d never known, and moved into a nice fourth-floor apartment at 1567 Calle Posadas. She was lucky--though she had really created her own luck--to have a guaranteed job in an industry where security is almost unknown. Eva was quite a celebrity by this time, and is remembered as a tough, but dependable worker. She was opportunistic, but those who accuse her of scheming megalomania ignore the fact that long-range planning was not her style. She picked the plums which were within reach and certainly had the drive and ambition to create a well-cushioned spot for herself in an industry still in its growth period, but she lived from day to day, although not hand-to-mouth any longer.

Greedy Officers Unite

The 13-year-old Conservative government fell in June 1943, ousted by a military junta which decided it was time to regulate many facets of commerce which had been allowed to proceed haphazardly. The radio stations were among the first segments of industry to feel the stranglehold of red tape in the new administration. All programs that weren’t either educational or inspirational were banned and this included soap operas.

Eva was in a quandry. She had four years to run on her contract with Radical Soap, and had three soap operas on the air. Wisely, she took an old idea--the historical dramas she did in 1939--and expanded them into a series about famous women of history. Her next step was to get a permit to perform on the air and government approval of her scripts and series. When she went to the office of posts and telegraphs, she met and became friends with the director, Col. Aníbal Imbert and his assistant, Oscar Nicolini. Through the remainder of 1943 and all of 1944, Eva did a tremendous amount of work on the radio and it’s not remarkable that she got to know these two officials well, though later, her detractors claimed one was an ex-lover of her mother’s and the other Eva’s lover. As it was, Eva’s friendship and gratitude for Nicolini’s help in easing her through the bureaucratic barriers woud have very important consequences later, but for now, Eva began her new series on September 21.

The oligarchs had been in power since Eva was a third-grader, and any group at the top of the power structure becomes a model and goal for those who hope to be socially mobile. Eva’s deep-seated hated of the landed aristocracy is supposed by many to have begun in her earliest years, but she had little contact with this class while in General Viamonte and Junín, and her early years in Buenos Aires had been the first chance she had to observe the wealthy porteños at work and play.

Eva could not have been sorry as she watched power change hands in 1943. She always said she wanted to be somebody, and it’s doubtful that any deep-seated convictions would have stopped her if she’d had a chance to insinuate herself into the upper class. After all, the only way to get ahead in the big city was with the approval--tacit or overt--of the class in power.

And that class in power had just changed. The group of colonels who rose to the surface after the junta were new to power, essentially middle class, and accessible, not hidebound to traditions and social credentials Eva would have found it hard if not impossible to fabricate. Initially, they were a seemingly homogeneous group who all belonged to a "club" known as the Grupo de Oficiales Unidos (United Officers Group), and they controlled the junta government from large and small posts.

The G.O.U. was begun in 1942 by eight officers who planned a new military lodge as a means of giving unity and expression to the younger officers. The power of the military in Argentine politics had begun long before the coup in 1943, since the backing of the armed forces was essential for the survival of most regimes.

The military already had Axis leanings in the late 1930s, since many of the officers had trained in Italy or Germany. The president who took office in 1940, Ramon Castillo, had furthered relations with Axis powers. The officer corps belief that popular government would lead to communism was also a reason the group of officers banded together with the stated aims of combating communism, promoting nationalism and solidifying the officer corps.

The original eight members of the G.O.U. also agreed on anonimity for themselves and outlawed personal ambition. There would eventually be 17 to 20 members of the group’s directive body and in spite of their intentions, two achieved personal prominence. Lt. Col. Enrique González and Col. Juan Domingo Perón were both alumni of the military academy in Argentina and had both trained in the great European war machines-- González in Germany and Perón in Italy.

The non-political tone of the first G.O.U. meetings soon evaporated and the group eventually (and unwittingly) became responsible for the military intervention of June 4, 1943, which ousted president Castillo from office. Castillo had been widely hated because of his complete disregard for both legality and the constitution, and he seemed to care even less about public opinion. Congress had no veto power, and the armed forces was the only group with enough power to stage a coup. The cadre of the G.O.U. may have agreed on its immediate objectives, but not about the sort of government which would replace Castillo if the coup was successful. They never even discussed who would head the provisional government.

It began with 10,000 troops marching on the capital, unopposed. The revolution was almost festive, with food kitchens sending out appetizing smells as they set up in the Plaza de Mayo to feed the troops and the gathering of porteños increased hourly after the word spread that something was happening. Enterprising vendors hawked their wares to the crowds. Though the youthful exuberance of the crowd and a common desire for a more viisible expression of the important event resulted in the burning of a few foreigh-owned buses, the crowd dispersed quietly at dinnertime, and the colonels settled down in the Casa Rosada.

Gen. Arturo Rawson, who had strong support in the navy--and a lot of ambition, simply walked into the president’s office and sat down. He began to select a cabinet before the other flabbergasted military leaders had even removed their tunics. Rawson’s move was so unexpected, it took them two days to toss him out. Correcting their earlier error, the G.O.U. set up a provisional government with Gen. Pedro Ramírez as president. His cabinet was pretty evenly split between pro-Axis and pro-Allies men, but the balance was negated by the group putting a pro-Axis or neutralist man in nearly every important governmental post. Juan Perón was appointed under-secretary to the new minister of war, Edelmiro Farrell.

Farrell immediately became a puppet minister and Perón quietly ran things from the murky background. He was wily enough to play his hand with discretion and even Farrell believed he still had some power. Perón began recruiting junior officers to the G.O.U. and the government soon shed its provisional title and cancelled scheduled elections.

Civil rights became a dim memory and the state of seige allowing the government to rule by decree was extended. The foreign policies of the Ramírez government were in a constant state of flux as he wavered time and again over the Axis/Allies problem. The blood ties with Italy that existed in Argentina made a decision to break off relations with Germany and Italy most unpopular. But there was also intense pressure from the U.S. and Brazil to join the Allies. And the U.S. had the power to upgrade the Argentine military materiel, which was sadly out of date.

In October 1943, a secret mission was sent to Berlin. The general staff decided America’s terms for rearmament were too severe and the Nazis offered arms in return for the continuation of food shipments and Argentina’s continued neutrality. This mission was doomed to failure, but there was enough pressure at home to worry Ramírez. The socialists and pro-Allies convinced him to fire Farrell and Perón but he changed his mind hours later. The G.O.U. then jumped in and forced him to promote Farrell to vice president and fire the remaining moderates from the cabinet. Ramírez’ vacillation turned into paranoia; he’d been ruling by decree since the beginning, with a complete suspension of constitutional guarantees. Repression of all opposition was the stated goal of the regime, but it had no clear-cut ideals, and did nothing to educate the masses. This proved to be a mistake, and one which separates Argentina’s brand of politics from the classical Nazi model. The regime was overconfident--it believed supression was enough.

Perón became head of the labor department in October. None of his colleagues could understand why he wanted the job, but within 30 days, he upgraded the department to a secretariat and created his first liasons with the people who would become his greatest power base--the labor unions.

The generals and colonels first became disenchanted with Perón (and frightened of his power) at the same time the masses discovered him. His anti-communist position was popular with junior officers but he began to antagonize important people when he nullified many of the president’s anti-union edicts and presented himself as an individualist. His bid for sole power was in direct contradiction to the G.O.U. bylaws, and Gonzáles (who was by now a cabinet minister) tried to get Perón out by proposing a party statute that no military man could seek office.

Go to: Chapter 3. EVA DUARTE AND JUAN PERÓN (1944-1945)

Bibliography

Design © 1999

Text© 1980, 1999 by Sylvia Stoddard