Those who wish to see clearly the entire picture

of life itself should see not only the highlights;

it is useful for them also to know the sorrows.

--Eva Perón, La razón de mi vida Evita

Despite the tenacity of her legend in her own country, Eva Perón was essentially forgotten by the world soon after the circus of her funeral was over.

Diamond Orchid (1964)

But for some, it wasn’t long before it was clear that the life of Eva Perón was the stuff of great drama. While touring South America, Jerome Lawrence, award-winning dramatist with Robert E. Lee of Inherit the Wind, The First Monday in October, Mame and many other plays, just happened to be flying from Santiago to Buenos Aires at the exact moment Eva died. As they landed at the airport, a moment of prayer was said for the dead first lady and Lawrence first faced "the roughest customs I’ve ever gone through...they examined every sock."

After bribing one of the scarce taxis available, Lawrence and his luggage were unceremoniously dumped blocks from his hotel. The streetlights were all draped in black crepe, and there were "people sobbing everywhere--people milling through the streets, a mad orgy of mourning."

The whole next week, Lawrence found everything in the city closed, and he walked the streets, observing the millions lined up in the rain to pass her casket and talking to those he could about why they loved her. The answer was always the same: the only freedom they had before was the freedom to starve, live in poverty.

Every shop window had its black-shrouded shrine to Evita. Everyone wore black arm bands. Everything was rigidly controlled--Lawrence even had trouble with guards several times when he tried to take photos. He could write only one thing to his parter, "What a great play there is in this woman, this whore who came to power...a great part for a great actress."

Lawrence and Lee eventually did write a Broadway play based on the Peróns called Diamond Orchid and it failed for that reason--the actress wasn’t great enough. After substantial research, including a meeting with Fleur Cowles, who had spent some time with Eva in Buenos Aires in her glory days and eventually wrote Bloody Precedent, published in America just before Eva died, who told them of the gaudy pin Eva loved--a five by seven-inch pure white diamond orchid brooch, they had their play’s name.

Delayed by other work, Lawrence and Lee didn’t get to polish the play until the early 1960s. They finished it and had a reading in Lawrence’s Malibu home--with Nina Foch and William Conrad. They loved the play, the dramatists’ agent loved the play and so did Broadway producers Gilbert Miller, Roger Stevens, Robert Whitehead and Alfred de Liagre.

Charles Laughton agreed to direct if they got a truly great actress. Vivien Leigh was interested and Lawrence and Lee wrote and rewrote the play for her, but she turned it down because she said they didn’t like the character and said, in a startlingly prescient statement, "Besides, it’s too rich. It should be an opera."

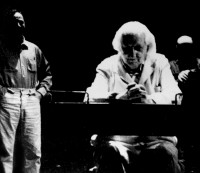

But Laughton became ill, producers came and went, and finally in 1964, the production was mounted, directed by José Quintero and starring an unknown, Jennifer West, who’d impressed everyone with her performance in an Off-Broadway play. The play’s characters were fictionalized and Eva and Juan became Paulita and Jorge Brazo. Realizing it was important to present the opposing side of the Perón smoke and mirror show in Argentina, they created an antagonist--a wise doctor, played by veteran actor Finlay Currie.

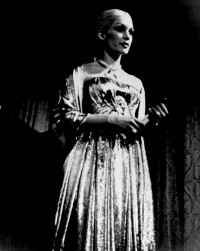

The play looked a lot like the later musical Evita, not surprising since both depict actual events. Lawrence and Lee did include a little more about Eva’s radio career, and her mother’s awkward adjustment to presidential palace life and luxurious clothes. There was also a wonderful scene where Eva has one of the ladies of the oligarcy to tea and is shown up for the ignorant, barefoot girl from the Pampas that she was. The balcony scenes were very much alike (though Lawrence and Lee ended the first act with theirs, while the musical opens the second act with it). Even the play’s poster has a silhouette of the glossy Eva, her arms raised in the familiar Evita pose.

The supporting cast was superb and Bruce Gordon, who played a member of the opposition party and one of Paulita's first powerful lovers, was excellent. But West’s inexperience showed, the play failed and closed within a few days.

Diamond Orchid opened February 10, 1965 at Henry Miller's Theatre. José Quintero directed, Costumes by Donald Brooks (see photos for Paulita's wonderfully dreadful dress when she first meets the doyenne of the oligarchs), Sets and Lighting by David Hayes, and starring Jennifer West as Paulita, Bruce Gordon as Maximiliano Orton (a politician eventually forced to flee from the Brazo dictatorship), Finlay Currie as Dr. Domingo Guzmano, Mario Alcalde as Jorge Salvador Brazo, Helen Craig as Mama, Margery Maude as Dona Elena Rivera, with Bruce Kirby, Leonardo Cimino, Louis Goss, Leon B. Stevens, Mel Haynes, Felice Orlandi, William Cottrell, John Garces, John Armstrong, Gerald McGonagill, Borah Silver, James Goodnow, Rene Enrique, Betty Hellman, Patricia Jenkins and Mary Bell. Lawrence says that after the opening night, renowned director Quintero sat on the edge of the stage of the empty theatre, his head in his hands, moaning, "She do nothing I tell her. Nothing."

Lawrence is pragmatic about it all. "We have play after play after play which later became something in another form...our production of Eva’s story was obviously fifteen years ahead of its time." He was pleased, however, when Tim Rice introduced him and Bob Lee to friends at the Broadway tryouts in Los Angeles as "the men who wrote the original."

Mission: Impossible TV Episode--November 24, 1968

The popular Paramount TV show occasionally used historical characters to enrich and inspire an episode. In the third season, Barbara Bain played an Anastasia (daughter of Russia’s last Tsar) character and several weeks later, the Impossible Mission Force is sent to the country of San Cordova where the country’s dictator has just died and his wife--always the power behind the throne--plans to stage a coup to prevent free elections ordered by the deputy premier.

Since (like Eva Perón) Riva Santel (played by Ruth Roman) has used the dictatorship’s propaganda machine to make her name and image the indelible badges of her power, her face is her fortune. She believes eternal beauty will lead to eternal power, and when she learns one of the IMF team (Rollin), there to film a documentary, is a miraculous plastic surgeon, she commands him to operate on her.

The episode is from the third season, #59, and is titled "The Elixer." It was written by Max Hodge and directed by John Florea. It first aired on November 24, 1968 and also starred Morgan Sterne, George Gaynes, Ivor Barry, Richard Angarola and Irene Kelly as the young Riva.

The producers acknowledge that Eva was the inspiration for this story, but the plot is actually quite different, with Eva and Juan essentially switching roles. The plastic surgery that goes wrong for Riva is ironic in sense that a medical man with a secret miracle permenantly preserved the real Eva's dead face and body in youth and beauty.

The episode is particularly memorable for the IMF’s final coup de grace, an especially sadistic and fitting one for the lady who wanted it all.

Eva Perón Paris--1970

An avant garde playwright named Copi dramatized Eva’s life in Paris in 1970. The play is mythic, allegorical and bizarre to say nothing of the fact that Eva was played by a man! On opening night, the audience was so incensed, they burned down the theatre. Eva does incite passions.

Argentine Film--1996 Eva Perón

At the same time that the Disney/Cingergi film production of the musical starring Madonna was in pre-production, an Argentine filmmaker put together his own movie--basically following the party line. However, it is a fascinating film, covering the days from the August 1951 rally where Eva hoped for the mandate to run for vice president until her death. Esther Goris turns in a stunning performance as the already ill Eva. The whole enterprise has--not surprisingly--the ring of authenticity. Private conversations between the First Couple seem more than plausible; they seem true. Whether these scenes were created from the knowledge that such conversations must have taken place or whether they were reported by servants or flunkies doesn't matter, they feel indelibly real. The relationship between Juan and Eva also feels realistic, knowing what we do now, though of course, the waning support of the descamisados and Perón's pedophilic actiivities are naturally not addressed. The acting is very good, the settings authentic or well recreated and the drama of the story has its usual impact. The film was proposed as Argentina's entry for the Oscars in America, but was not nominated.

Go to: THE MUSICAL'S LONG ROAD TO FILM

Bibliography

Design © 1999

Text ©1980, 1999 by Sylvia Stoddard