|

A Journey Down $un$set B£vd.

By Sylvia Stoddard

Originally appeared in Show Music, Fall 1993 © 1993

[Andrew Lloyd Webber, at the time of publication, possessed the OBE and was Sir Andrew. He is now Andrew,

Lord of Sydmonton.]

_______

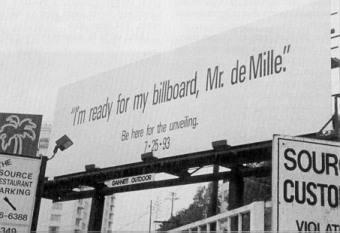

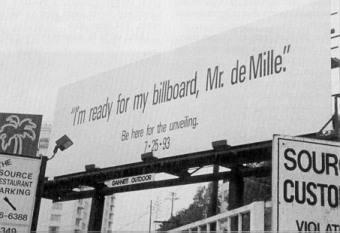

The week Andrew Lloyd Webber's Sunset Boulevard began previews in London, a large billboard went up on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles. It read:

"I'm ready for my billboard, Mr. deMille."

Be here for the unveiling.

7-25-93

The idea that anyone would be interested in a billboard unveiling--and the mis-capitalization and

incorrect spacing of Cecil B. De Mille's name--speaks volumes about how and why Sunset Boulevard

was created. It seems the musical that premiered July 12 at London's Adelphi Theatre was shaped more

by Andrew Lloyd Webber's financial situation than by any of its creators.

The composer of Evita, Cats and The Phantom of the Opera has a vast personal fortune

which is not in jeopardy. But like most astute entrepreneurs, Sir Andrew keeps his business interests

separate, and it is these which are affected. In 1986, Lloyd Webber founded the Really Useful Group (RUG),

a public corporation that was to share in the profits from his composing work until 1993. The board was

composed of longtime associates and advisors, including his ex-partner Tim Rice, a non-executive director

of the company.

In 1989, a major boardroom clash, reportedly over diversification, caused the departure of Brian Brolly,

co-founder and respected CEO of Really Useful. Rice left the company at the same time. The London

financial community was disturbed, but Lloyd Webber's former personal assistant, Bridget 'Biddy' Hayward,

had become an accomplished producer and was still in place. Then, in 1990, Sir Andrew announced that he

was shifting his attention to film production and that Aspects of Love might be his last stage musical

for some time. Because of this, Lloyd Webber no longer wanted to have to answer to his shareholders and

planned to buy back all shares in his company for around £80 million.

It wasn't a smooth transition. At the last minute, Robert Holmes à Court--owner of 13 West End theatres--bought a 6.61% stake in Really Useful, preventing Sir Andrew from gaining the 95% of shares needed to compel the remaining shareholders to sell. Holmes à Court reportedly wanted to use the stock to get control of the Palace Theatre, which Really Useful lovingly restored and which houses its offices. It was a stalemate until Holmes à Court died of a heart attack. The family decided to keep its theatre holdings but the power play was over. Lloyd Webber got his company back.

One year later, the resulting debt proved to be crippling to RUG's operations and Lloyd Webber sold 30% of the company to European recording giant PolyGram for £68 million plus future monies said to be proportional to Really Useful's profit margin. Lloyd Webber no longer had to answer to shareholders and financial analysts, but he had to answer to PolyGram. This time, his composing, film and producing work were tied up in the agreement, now in effect until 2003.

The money coming in to RUG from Lloyd Webber's past hits must be substantial, but the balance sheet really needed a new show on the boards and making money before the end of 1993. There are rumors that if profits do not reach a certain level, RUG will have deeper problems.

It would seem that Sunset Boulevard was created specifically to stave off the PolyGram threat.

Until recently any Lloyd Webber show was critic-proof. His only real failure had been Jeeves, which closed after five weeks in 1975. Each show became a money machine, spawning companies around the world, recordings in many languages and profitable merchandise.

Aspects, Lloyd Webber's most recent show, made it into the profit column in its three-year London run,

but the Broadway production was a 10-month failure and just one North American touring company has been mounted. Lloyd Webber's foray into film production faltered, with several directors and starting dates announced for the film version of Phantom before the project was put on hold. Several attempts to put Evita on film stalled as well. Fifteen years earlier Lloyd Webber had first thought of converting the classic film Sunset Boulevard into a stage musical, and that became the project to which he turned his attention. Several major musical theatre talents had considered musicalizing the film over the years, including Stephen Sondheim and Hal Prince, but it was Lloyd Webber who acquired the rights in 1990.

Based on Billy Wilder's revered 1950 film, Sunset Boulevard is a perfect vehicle for the Lloyd Webber hit machine, among the greatest of Hollywood's movies about itself. Set in 1949-1950, it is the story of Norma Desmond, a relic of the early years of filmmaking. When talkies pushed silent films and their stars out of the limelight, Norma locked herself into her mansion with her memories, a servile ex-husband and a chimp as her only companions. Twenty years later, when disillusioned screenwriter Joe Gillis happens to stumble within her reach, Norma clutches his vitality to her with a death grip.

Though Joe Gillis becoming Norma Desmond's boy-toy is not at all scandalous today, the movie's appeal lies in its flawless performances, masterful direction and the mood of moldy horror which clings to the story like moss on Norma's crumbling mansion. The atmospheric score by Franz Waxman contributes greatly to the film's emotional appeal.

In 1991 Lloyd Webber asked New York lawyer Amy Powers to write the lyrics for Sunset Boulevard.

Powers had no professional lyric-writing experience. As that year's Sydmonton Festival approached, Lloyd

Webber seemed to become worried and brought in Don Black, who had written lyrics for Tell Me on a

Sunday and collaborated on Aspects, to work with Powers. Sydmonton Court is Lloyd Webber's vast

estate on the edge of Watership Down in Berkshire. Since 1975 the composer has held an arts festival each

year in early September, often featuring new works by other composers and dramatis,ts but primarily as a

venue for the first performance of Lloyd Webber's own work before a carefully selected, discreet audience.

However, the first presentation of Sunset Boulevard was not a success.

With production of the musical scheduled for 1993, Powers was out, Black stayed on and Lloyd Webber hired

Christopher Hampton to co-write the book and lyrics. Academy Award-winner Hampton had written a play

called Tales from Hollywood and adapted Les Liasons Dangereuses for stage and film. A

revised Sunset Boulevard was presented at Sydmonton in September 1992, with Patti LuPone and

Kevin Anderson, and met with great success.

The sure-fire elements were all there. Lloyd Webber had previously created an ominous, brooding score for Evita and had LuPone, its American star, to play Norma. Although too young for the role Swanson played when she was 50, LuPone had the presence, theatricality and vocal power to pull it off. Kevin Anderson, playing Joe Gillis, had recently starred in several high-visibility films, including Sleeping with the Enemy and Hoffa. It seemed Lloyd Webber was in his usual win-win situation.

He wanted the show to open in June 1993 in the city where the story was set--Los Angeles. But when it seemed the Shubert Theatre's remodeling (at Lloyd Webber's request) wouldn't be done on time (it actually was), he pulled the world premiere from L.A. Instead, Lloyd Webber bought and remodeled a theatre in London. It wasn't ready on time and two weeks of previews had to be cancelled, creating administrative problems and a great deal of bad feeling among theatregoers. Los Angeles would get the American premiere, starring Glenn Close, in December 1993.

Lloyd Webber originally sought Hal Prince to direct Sunset. Prince had masterfully shaped Evita and Phantom for the theatre and seems to have a special touch with Lloyd Webber material. But Prince had other commitments for 1993, and without Prince there seemed to be no one around Lloyd Webber who was powerful or respected enough to give him an honest opinion. Brian Brolly and Tim Rice were gone, and in 1990, Sir Andrew lost his astute partner and producer, Biddy Hayward, unceremoniously fired after 17 years. A number of other Really Useful people left with Hayward, more loyal to her than to him.

Then RSC director Trevor Nunn was hired by Lloyd Webber. Nunn had directed Cats, which was a worldwide smash, though primarily because of Gillian Lynne's choreography and John Napier's sets. Lloyd Webber has frequently stated he disliked what Nunn did with Starlight Express, and Nunn had directed Aspects, the least successful of Lloyd Webber's hits, which had been ignored by the prestigious Olivier Awards in London. On Broadway, in spite of a $12 million advance, it lost its entire $8 million capitalization, surpassing mega-flop Carrie as Broadway's costliest failure. Nunn also had a failure with Tim Rice's Chess on Broadway, the hit show from London ran barely three months in New York.

The powerful Really Useful publicity machine ground into high gear earlier this year when tickets to the West End Sunset Boulevard were put on sale by phone chargeline-but only to Americans. To create a big, newsworthy event at home, RUG required Londoners to queue up at a single box office. The tabloids obediently covered this non-event. Really Useful wanted a big advance sale and that was one way to get it. After all, if Sunset Boulevard had a big enough advance, it didn't matter what anyone thought of the show. But London's theatregoers didn't respond with their usual alacrity at the Lloyd Webber name on the marquee and no casting had been announced. Maybe it was the recession or maybe it was because the public had bought tickets to Aspects and didn't like it. By Sunset Boulevard's first preview on June 28 (June 29 had been scheduled as the original opening night) the advance was small £3 million with a top ticket price of £32.50. Compare that with Miss Saigon's £5 million advance four years before, with a top ticket of £22.50, and its New York advance of $35 million. All of a sudden it did matter what everyone thought. (Even after Sunset Boulevard's opening, The New York Times' Frank Rich reported tickets were available.)

Sunset Boulevard had the first truly international premiere, invitations were extended to American critics as well as local ones. Still, the only unqualified rave was from The Wall Street Journal, with several of the London critics giving the show qualified raves. The rest were mixed, with an outright negative review from the Evening Standard's Nicholas de Jongh. Rich wrote a somewhat positive review for The New York Times, calling the score's 'surprisingly dark, jazz-accented music the most interesting I've yet encountered from this composer.' Everyone except Rich heaped praise on LuPone for her performance; Kevin Anderson received a more varied reception.

Lloyd Webber's music also received mixed notices: 'the most dramatically integrated score' (The Wall Street Journal); 'unmemorable, slowing down the action' (Daily Telegraph); 'understated, elegant melodies' (USA Today); 'surprisingly, the music is something of a disappointment' (Daily Express); 'a score that repeatedly takes the soft option' (Variety); 'enchanting to hear' (Times); 'Lloyd Webber's poundingly romantic score sentimentalizes the story by its palpable devotion to Norma Desmond' (Guardian); 'it's very…well…very Lloyd Webberish' (Today).

The Hollywood Reporter noted that Norma Desmond sings 'a lovely ballad about how she gave the world

new ways to dream,' yet wondered what it was doing in this show and commented that Lloyd Webber's music

didn't match the tone of the dialogue. Its review also complained that nothing in the music or lyrics 'seemed to

jibe' with the first image of Joe Gillis face down in Norma's swimming pool. Variety said the composer's music was missing 'the ferocity, the irony, the sardonic comedy' of the original piece and that the musical failed to find its own voice. One critic thought he heard 'Paganini, Puccini and the usual crew' in the score, but most noticed Lloyd Webber was now stealing from himself.

In several interviews within the last year, Lloyd Webber has explained the deviation from his announced plan of forsaking the theatre for films and literary endeavors because 'suddenly the composing urge came back.' The truth is, he has composed virtually nothing new for Sunset Boulevard.

Nearly its entire score is from Lloyd Webber's trunk. A majority of the songs were written years ago, many published, recorded or performed with lyrics by Tim Rice. Lloyd Webber has always drawn from his trunk, as do many composers. 'I Don't Know How to Love Him' was written as 'Kansas Morning' long before Lloyd Webber and Rice started work on Jesus Christ Superstar. Phantom contains several trunk songs. 'Music of the Night' was originally 'Married Man,' a song Lloyd Webber wrote--with his own besotted lyric--about his love for Sarah Brightman, who sang the song on a 1983 Merv Griffin Show appearance; 'All I Ask of You' was first heard as 'I Don't Talk to Strangers' (lyric by Rice), written for and performed by Placido Domingo on a 1985 television special.

More songs emerged from the trunk for Aspects, including two songs from Cricket, a 30-minute show Rice and Lloyd Webber wrote for the Queen's birthday in 1985. It is a charming love story with sporting interruptions all set during one summer Sunday afternoon, with at least five memorable melodies and literate lyrics. It is a tantalizing glimpse of what the ex-partners could create today.

But Sunset Boulevard is nothing like Cricket in mood, period or emotional level. Yet, 'As If We Never Said Goodbye,' Norma's big second act number, was Cricket's love song, 'Lazy Days of Summer.' Norma's first act showstopper, 'With One Look,' is reminiscent in places of 'Will This Last Forever?' from Lloyd Webber and Rice's first show, The Likes of Us (Lloyd Webber also raided this unproduced piece for music for both Variations and Aspects).

The melody for Sunset Boulevard's title song has had several incarnations, including a song called 'Finally' (lyrics by Rice) recorded in the 1960s by Pamela Patterson and then used as a theme in Lloyd Webber's 1974 film score for The Odessa File. Other music from that score is heard in Sunset Boulevard along with melodies from another Lloyd Webber film score for 1972's Gumshoe.

Sunset Boulevard's songs sound like melodies from six different places and several different decades because that's exactly what they are. There's a faux feeling about the score, as if it's dummy music temporarily laid in until the real score is finished. In fact, the score feels a little like those for shows created around the existing work of a deceased composer where the songs don't quite fit, clearly a result of the various sources of the melodies.

It seems as if no attempt was made to establish a mood or period for Lloyd Webber's Sunset Boulevard score. Each song is still in the tempo and style in which it was originally written--the only cohesive element in the score is the orchestration. The film's score sets a brooding, dark mood hinting at insanity and futility, the spooky wheezing of Norma's pipe organ adding dread to even the most innocuous scenes. Only one of Lloyd Webber's melodies, 'The Greatest Star of All,' has exactly the qualities the whole score needs. It is haunting, with interesting phrasing and harmonies, but its power is diffused by exposition-heavy lyrics about Norma's career.

That may be the result of Lloyd Webber's well-documented inclination to control every aspect of his productions, most clearly evident in the ever-deteriorating quality of the lyrics in his recent shows. He no longer has collaborators, he hires lyric writers. Starlight Express, Phantom, Aspects, and now Sunset have all been criticized for lyrics which range from acceptable to clichéd. Compounding the problem, Sunset Boulevard is not so much a through-sung show as one with songs and recitative, like Aspects and Miss Saigon. This disturbing trend of sung dialogue tends to turn a one-page scene into four, the rhythmic singing taking longer than natural speech. Most of Sunset's dialogue is sung to six or eight notes from the previous song, which becomes tedious and has a tendency to be numbing.

Equally problematic is an opening number with starlets and writers singing 'Let's have lunch, 'how's it hanging?'

and 'we should talk,' conveying neither the 1950s nor the behind-the-scenes nature of the story. Repeated

references to 'Cecil B' (nobody called De Mille anything but C.B. or Mr. De Mille), 'Darryl' (Zanuck), (William)

'Fox,' (George) 'Cukor,' and (Adolph) 'Zukor' are meaningless to a non-industry audience and a lame attempt

at insiders talk, resulting in nothing more than a tourist's-eye view of Hollywood. Another song's list-like lyric

is an inventory of clothing presented for Joe's approval, and a third repetitive song is a litany of hackneyed

dreams masquerading as New Year's resolutions. None of these numbers has any subtext, advances the

plot or gives insight into the main characters.

'With One Look,' Sunset Boulevard's showstopper and the score's most dramatic song, is a reiteration of the famous line that precedes it, Norma's 'I am big. It's the pictures that got small.' Unfortunately, 'With One Look' occurs less than 20 minutes into the show and Norma is left without another moment of equal power.

The character of Joe Gillis is saddled with the title song, which opens the show's second act. Though the critics liked it, it is lyrically awkward, its music placing the emphasis on 'BOUL-e-vard,' which robs the word of its sense. In any case, it's the word 'sunset' which has a double meaning in the story and which should inspire the lyricist. It is apparent that the melody for this number was already written and when the needed lyric was applied to it the emphasis was wrong.

The same thing happens with Norma's second act number, 'As If We Never Said Goodbye,' her song on the soundstage of De Mille's current film. The lines that should be in the verse end up in the refrain and are wrongly emphasized by the music. It isn't surprising, as the melody was originally used for the main love song in Rice and Lloyd Webber's Cricket. Rice's original lyric for this melody is sung by the hero and the woman he loves as they realize they've been looking for the wrong things in their relationship:

I'll never make another confident prediction

Except for one, all's said and done, worth hearing

That the narrow minds of morning will be breaking out this evening

Oh, life can change in one hot afternoon

-Cricket

Norma's lines for the same melody are difficult to sing, Rice's lyrical and simple, the melody properly emphasizing the lyrics, which are strong on vowel sounds instead of consonants. It also has subtext.

No song is used for the famous ending of Sunset Boulevard, though this would seem the perfect place for one. The melodies of 'With One Look' and 'As If We Never Said Goodbye' mingle for Norma's famous walk down the stairs, with an interval when she sings a line from each of the show's songs, reliving her love affair with Joe. It's an ending that fails to satisfy either dramatically or musically (and we already saw that in Evita).

It would seem the only reason to turn Sunset Boulevard into a musical would be to explore the characters in ways that can't be done with mere words. Who are these people, what do they feel and how do they change? If you compare musicals like Carousel, Oklahoma!, South Pacific or My Fair Lady to their source material, it is clear the composers, book writers and lyricists brought new insights to those stories, along with the songs. As Sunset Boulevard illustrates, the same thing can't be accomplished through a patchwork quilt of a score with lyrics forced on existing melodies.

Interestingly, Sunset will be competing for audiences and awards with an acclaimed revival of Rodgers and Hammerstein's Carousel, both in London and in New York. The contrast couldn't be greater. For instance, Nicholas de Jongh's Evening Standard review of London's Carousel began 'I never knew a musical from the conformist 1940s could have so much danger and daring in it.' Perhaps that's what is missing most from Sunset Boulevard.

Andrew Lloyd Webber is one of the giants of today's global musical theatre. A new work from him is an event, but the public has a right to expect to get their 33 quid or 65 bucks' worth. They have a right to expect it to contain a score to which he's devoted considerable time. How they will react to the patched-together Sunset Boulevard, whether making it a big hit, a limited hit like Aspects, or a failure, remains to be seen.

• classic tv books

• dvds

• articles

• tv episode guides

The composer of Evita, Cats and The Phantom of the Opera has a vast personal fortune which is not in jeopardy. But like most astute entrepreneurs, Sir Andrew keeps his business interests separate, and it is these which are affected. In 1986, Lloyd Webber founded the Really Useful Group (RUG), a public corporation that was to share in the profits from his composing work until 1993. The board was composed of longtime associates and advisors, including his ex-partner Tim Rice, a non-executive director of the company.

In 1989, a major boardroom clash, reportedly over diversification, caused the departure of Brian Brolly, co-founder and respected CEO of Really Useful. Rice left the company at the same time. The London financial community was disturbed, but Lloyd Webber's former personal assistant, Bridget 'Biddy' Hayward, had become an accomplished producer and was still in place. Then, in 1990, Sir Andrew announced that he was shifting his attention to film production and that Aspects of Love might be his last stage musical for some time. Because of this, Lloyd Webber no longer wanted to have to answer to his shareholders and planned to buy back all shares in his company for around £80 million.

It wasn't a smooth transition. At the last minute, Robert Holmes à Court--owner of 13 West End theatres--bought a 6.61% stake in Really Useful, preventing Sir Andrew from gaining the 95% of shares needed to compel the remaining shareholders to sell. Holmes à Court reportedly wanted to use the stock to get control of the Palace Theatre, which Really Useful lovingly restored and which houses its offices. It was a stalemate until Holmes à Court died of a heart attack. The family decided to keep its theatre holdings but the power play was over. Lloyd Webber got his company back.

One year later, the resulting debt proved to be crippling to RUG's operations and Lloyd Webber sold 30% of the company to European recording giant PolyGram for £68 million plus future monies said to be proportional to Really Useful's profit margin. Lloyd Webber no longer had to answer to shareholders and financial analysts, but he had to answer to PolyGram. This time, his composing, film and producing work were tied up in the agreement, now in effect until 2003.

The money coming in to RUG from Lloyd Webber's past hits must be substantial, but the balance sheet really needed a new show on the boards and making money before the end of 1993. There are rumors that if profits do not reach a certain level, RUG will have deeper problems.

It would seem that Sunset Boulevard was created specifically to stave off the PolyGram threat.

Until recently any Lloyd Webber show was critic-proof. His only real failure had been Jeeves, which closed after five weeks in 1975. Each show became a money machine, spawning companies around the world, recordings in many languages and profitable merchandise.

Aspects, Lloyd Webber's most recent show, made it into the profit column in its three-year London run, but the Broadway production was a 10-month failure and just one North American touring company has been mounted. Lloyd Webber's foray into film production faltered, with several directors and starting dates announced for the film version of Phantom before the project was put on hold. Several attempts to put Evita on film stalled as well. Fifteen years earlier Lloyd Webber had first thought of converting the classic film Sunset Boulevard into a stage musical, and that became the project to which he turned his attention. Several major musical theatre talents had considered musicalizing the film over the years, including Stephen Sondheim and Hal Prince, but it was Lloyd Webber who acquired the rights in 1990.

Based on Billy Wilder's revered 1950 film, Sunset Boulevard is a perfect vehicle for the Lloyd Webber hit machine, among the greatest of Hollywood's movies about itself. Set in 1949-1950, it is the story of Norma Desmond, a relic of the early years of filmmaking. When talkies pushed silent films and their stars out of the limelight, Norma locked herself into her mansion with her memories, a servile ex-husband and a chimp as her only companions. Twenty years later, when disillusioned screenwriter Joe Gillis happens to stumble within her reach, Norma clutches his vitality to her with a death grip.

Though Joe Gillis becoming Norma Desmond's boy-toy is not at all scandalous today, the movie's appeal lies in its flawless performances, masterful direction and the mood of moldy horror which clings to the story like moss on Norma's crumbling mansion. The atmospheric score by Franz Waxman contributes greatly to the film's emotional appeal.

In 1991 Lloyd Webber asked New York lawyer Amy Powers to write the lyrics for Sunset Boulevard. Powers had no professional lyric-writing experience. As that year's Sydmonton Festival approached, Lloyd Webber seemed to become worried and brought in Don Black, who had written lyrics for Tell Me on a Sunday and collaborated on Aspects, to work with Powers. Sydmonton Court is Lloyd Webber's vast estate on the edge of Watership Down in Berkshire. Since 1975 the composer has held an arts festival each year in early September, often featuring new works by other composers and dramatis,ts but primarily as a venue for the first performance of Lloyd Webber's own work before a carefully selected, discreet audience. However, the first presentation of Sunset Boulevard was not a success.

With production of the musical scheduled for 1993, Powers was out, Black stayed on and Lloyd Webber hired Christopher Hampton to co-write the book and lyrics. Academy Award-winner Hampton had written a play called Tales from Hollywood and adapted Les Liasons Dangereuses for stage and film. A revised Sunset Boulevard was presented at Sydmonton in September 1992, with Patti LuPone and Kevin Anderson, and met with great success.

The sure-fire elements were all there. Lloyd Webber had previously created an ominous, brooding score for Evita and had LuPone, its American star, to play Norma. Although too young for the role Swanson played when she was 50, LuPone had the presence, theatricality and vocal power to pull it off. Kevin Anderson, playing Joe Gillis, had recently starred in several high-visibility films, including Sleeping with the Enemy and Hoffa. It seemed Lloyd Webber was in his usual win-win situation.

Lloyd Webber originally sought Hal Prince to direct Sunset. Prince had masterfully shaped Evita and Phantom for the theatre and seems to have a special touch with Lloyd Webber material. But Prince had other commitments for 1993, and without Prince there seemed to be no one around Lloyd Webber who was powerful or respected enough to give him an honest opinion. Brian Brolly and Tim Rice were gone, and in 1990, Sir Andrew lost his astute partner and producer, Biddy Hayward, unceremoniously fired after 17 years. A number of other Really Useful people left with Hayward, more loyal to her than to him.

Then RSC director Trevor Nunn was hired by Lloyd Webber. Nunn had directed Cats, which was a worldwide smash, though primarily because of Gillian Lynne's choreography and John Napier's sets. Lloyd Webber has frequently stated he disliked what Nunn did with Starlight Express, and Nunn had directed Aspects, the least successful of Lloyd Webber's hits, which had been ignored by the prestigious Olivier Awards in London. On Broadway, in spite of a $12 million advance, it lost its entire $8 million capitalization, surpassing mega-flop Carrie as Broadway's costliest failure. Nunn also had a failure with Tim Rice's Chess on Broadway, the hit show from London ran barely three months in New York.

The powerful Really Useful publicity machine ground into high gear earlier this year when tickets to the West End Sunset Boulevard were put on sale by phone chargeline-but only to Americans. To create a big, newsworthy event at home, RUG required Londoners to queue up at a single box office. The tabloids obediently covered this non-event. Really Useful wanted a big advance sale and that was one way to get it. After all, if Sunset Boulevard had a big enough advance, it didn't matter what anyone thought of the show. But London's theatregoers didn't respond with their usual alacrity at the Lloyd Webber name on the marquee and no casting had been announced. Maybe it was the recession or maybe it was because the public had bought tickets to Aspects and didn't like it. By Sunset Boulevard's first preview on June 28 (June 29 had been scheduled as the original opening night) the advance was small £3 million with a top ticket price of £32.50. Compare that with Miss Saigon's £5 million advance four years before, with a top ticket of £22.50, and its New York advance of $35 million. All of a sudden it did matter what everyone thought. (Even after Sunset Boulevard's opening, The New York Times' Frank Rich reported tickets were available.)

Sunset Boulevard had the first truly international premiere, invitations were extended to American critics as well as local ones. Still, the only unqualified rave was from The Wall Street Journal, with several of the London critics giving the show qualified raves. The rest were mixed, with an outright negative review from the Evening Standard's Nicholas de Jongh. Rich wrote a somewhat positive review for The New York Times, calling the score's 'surprisingly dark, jazz-accented music the most interesting I've yet encountered from this composer.' Everyone except Rich heaped praise on LuPone for her performance; Kevin Anderson received a more varied reception.

Lloyd Webber's music also received mixed notices: 'the most dramatically integrated score' (The Wall Street Journal); 'unmemorable, slowing down the action' (Daily Telegraph); 'understated, elegant melodies' (USA Today); 'surprisingly, the music is something of a disappointment' (Daily Express); 'a score that repeatedly takes the soft option' (Variety); 'enchanting to hear' (Times); 'Lloyd Webber's poundingly romantic score sentimentalizes the story by its palpable devotion to Norma Desmond' (Guardian); 'it's very…well…very Lloyd Webberish' (Today).

The Hollywood Reporter noted that Norma Desmond sings 'a lovely ballad about how she gave the world new ways to dream,' yet wondered what it was doing in this show and commented that Lloyd Webber's music didn't match the tone of the dialogue. Its review also complained that nothing in the music or lyrics 'seemed to jibe' with the first image of Joe Gillis face down in Norma's swimming pool. Variety said the composer's music was missing 'the ferocity, the irony, the sardonic comedy' of the original piece and that the musical failed to find its own voice. One critic thought he heard 'Paganini, Puccini and the usual crew' in the score, but most noticed Lloyd Webber was now stealing from himself.

In several interviews within the last year, Lloyd Webber has explained the deviation from his announced plan of forsaking the theatre for films and literary endeavors because 'suddenly the composing urge came back.' The truth is, he has composed virtually nothing new for Sunset Boulevard.

Nearly its entire score is from Lloyd Webber's trunk. A majority of the songs were written years ago, many published, recorded or performed with lyrics by Tim Rice. Lloyd Webber has always drawn from his trunk, as do many composers. 'I Don't Know How to Love Him' was written as 'Kansas Morning' long before Lloyd Webber and Rice started work on Jesus Christ Superstar. Phantom contains several trunk songs. 'Music of the Night' was originally 'Married Man,' a song Lloyd Webber wrote--with his own besotted lyric--about his love for Sarah Brightman, who sang the song on a 1983 Merv Griffin Show appearance; 'All I Ask of You' was first heard as 'I Don't Talk to Strangers' (lyric by Rice), written for and performed by Placido Domingo on a 1985 television special.

More songs emerged from the trunk for Aspects, including two songs from Cricket, a 30-minute show Rice and Lloyd Webber wrote for the Queen's birthday in 1985. It is a charming love story with sporting interruptions all set during one summer Sunday afternoon, with at least five memorable melodies and literate lyrics. It is a tantalizing glimpse of what the ex-partners could create today.

But Sunset Boulevard is nothing like Cricket in mood, period or emotional level. Yet, 'As If We Never Said Goodbye,' Norma's big second act number, was Cricket's love song, 'Lazy Days of Summer.' Norma's first act showstopper, 'With One Look,' is reminiscent in places of 'Will This Last Forever?' from Lloyd Webber and Rice's first show, The Likes of Us (Lloyd Webber also raided this unproduced piece for music for both Variations and Aspects).

Sunset Boulevard's songs sound like melodies from six different places and several different decades because that's exactly what they are. There's a faux feeling about the score, as if it's dummy music temporarily laid in until the real score is finished. In fact, the score feels a little like those for shows created around the existing work of a deceased composer where the songs don't quite fit, clearly a result of the various sources of the melodies.

It seems as if no attempt was made to establish a mood or period for Lloyd Webber's Sunset Boulevard score. Each song is still in the tempo and style in which it was originally written--the only cohesive element in the score is the orchestration. The film's score sets a brooding, dark mood hinting at insanity and futility, the spooky wheezing of Norma's pipe organ adding dread to even the most innocuous scenes. Only one of Lloyd Webber's melodies, 'The Greatest Star of All,' has exactly the qualities the whole score needs. It is haunting, with interesting phrasing and harmonies, but its power is diffused by exposition-heavy lyrics about Norma's career.

That may be the result of Lloyd Webber's well-documented inclination to control every aspect of his productions, most clearly evident in the ever-deteriorating quality of the lyrics in his recent shows. He no longer has collaborators, he hires lyric writers. Starlight Express, Phantom, Aspects, and now Sunset have all been criticized for lyrics which range from acceptable to clichéd. Compounding the problem, Sunset Boulevard is not so much a through-sung show as one with songs and recitative, like Aspects and Miss Saigon. This disturbing trend of sung dialogue tends to turn a one-page scene into four, the rhythmic singing taking longer than natural speech. Most of Sunset's dialogue is sung to six or eight notes from the previous song, which becomes tedious and has a tendency to be numbing.

Equally problematic is an opening number with starlets and writers singing 'Let's have lunch, 'how's it hanging?' and 'we should talk,' conveying neither the 1950s nor the behind-the-scenes nature of the story. Repeated references to 'Cecil B' (nobody called De Mille anything but C.B. or Mr. De Mille), 'Darryl' (Zanuck), (William) 'Fox,' (George) 'Cukor,' and (Adolph) 'Zukor' are meaningless to a non-industry audience and a lame attempt at insiders talk, resulting in nothing more than a tourist's-eye view of Hollywood. Another song's list-like lyric is an inventory of clothing presented for Joe's approval, and a third repetitive song is a litany of hackneyed dreams masquerading as New Year's resolutions. None of these numbers has any subtext, advances the plot or gives insight into the main characters.

'With One Look,' Sunset Boulevard's showstopper and the score's most dramatic song, is a reiteration of the famous line that precedes it, Norma's 'I am big. It's the pictures that got small.' Unfortunately, 'With One Look' occurs less than 20 minutes into the show and Norma is left without another moment of equal power.

The character of Joe Gillis is saddled with the title song, which opens the show's second act. Though the critics liked it, it is lyrically awkward, its music placing the emphasis on 'BOUL-e-vard,' which robs the word of its sense. In any case, it's the word 'sunset' which has a double meaning in the story and which should inspire the lyricist. It is apparent that the melody for this number was already written and when the needed lyric was applied to it the emphasis was wrong.

The same thing happens with Norma's second act number, 'As If We Never Said Goodbye,' her song on the soundstage of De Mille's current film. The lines that should be in the verse end up in the refrain and are wrongly emphasized by the music. It isn't surprising, as the melody was originally used for the main love song in Rice and Lloyd Webber's Cricket. Rice's original lyric for this melody is sung by the hero and the woman he loves as they realize they've been looking for the wrong things in their relationship:

Except for one, all's said and done, worth hearing

That the narrow minds of morning will be breaking out this evening

Oh, life can change in one hot afternoon

No song is used for the famous ending of Sunset Boulevard, though this would seem the perfect place for one. The melodies of 'With One Look' and 'As If We Never Said Goodbye' mingle for Norma's famous walk down the stairs, with an interval when she sings a line from each of the show's songs, reliving her love affair with Joe. It's an ending that fails to satisfy either dramatically or musically (and we already saw that in Evita).

It would seem the only reason to turn Sunset Boulevard into a musical would be to explore the characters in ways that can't be done with mere words. Who are these people, what do they feel and how do they change? If you compare musicals like Carousel, Oklahoma!, South Pacific or My Fair Lady to their source material, it is clear the composers, book writers and lyricists brought new insights to those stories, along with the songs. As Sunset Boulevard illustrates, the same thing can't be accomplished through a patchwork quilt of a score with lyrics forced on existing melodies.

Interestingly, Sunset will be competing for audiences and awards with an acclaimed revival of Rodgers and Hammerstein's Carousel, both in London and in New York. The contrast couldn't be greater. For instance, Nicholas de Jongh's Evening Standard review of London's Carousel began 'I never knew a musical from the conformist 1940s could have so much danger and daring in it.' Perhaps that's what is missing most from Sunset Boulevard.

Andrew Lloyd Webber is one of the giants of today's global musical theatre. A new work from him is an event, but the public has a right to expect to get their 33 quid or 65 bucks' worth. They have a right to expect it to contain a score to which he's devoted considerable time. How they will react to the patched-together Sunset Boulevard, whether making it a big hit, a limited hit like Aspects, or a failure, remains to be seen.

• classic tv books |

• dvds |

• articles |

• tv episode guides |